The spread of the coronavirus in Africa has exposed the precarious nature of many of its healthcare systems. I am writing this at a fraught time in the history of public healthcare on the continent.

A pre-COVID-19 survey by Afrobarometer, an online data analysis tool, found that one in five

Africans faced a frequent lack of much-needed healthcare services.

Africa’s investment in health has repeatedly been called out but little has been done to boost financial investment. Now, the chickens have come home to roost.

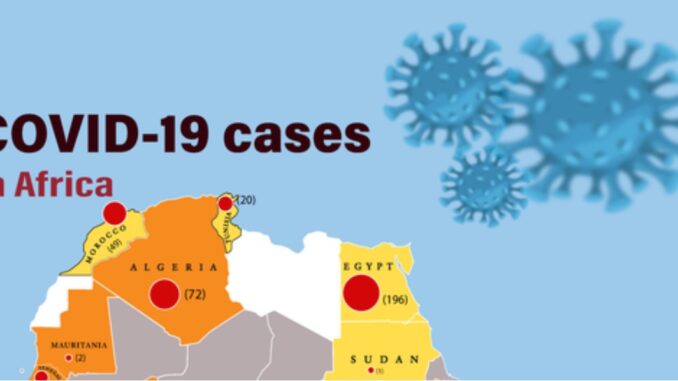

The number of those suffering from the coronavirus is still low compared to what has been witnessed in the United States, Britain, Europe and even Asia. Africa was the last frontier in the incipient spread of the virus.

The first coronavirus case was reported on the continent on February 14 in Egypt. On March 18, the first case in sub-Saharan Africa was reported in Nigeria.

The slow spread on the continent gave false hope that Africa and its people would be spared the worst of the pandemic. But when it started to spread, the reality sunk in fast. It exposed what we had always known for a long time. Most of Africa’s healthcare systems are not adequately equipped and their fragility is one outbreak away from a total nightmare.

The initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic by individual countries in Africa was swift. Travel restrictions, total lockdowns and even curfews have been applied by different authorities.

Rwanda, for instance, announced an immediate lockdown, and has been supplying water and food to its vulnerable populations; South Africa announced a national lockdown and set in motion dozens of mobile testing units, with a combined daily testing capacity of 30,000. Nigeria has extended its lockdown in Lagos and Abuja.

Kenya, on the other hand, instituted a nationwide dawn-to-dusk curfew, while limiting movement within its capital city and the environments to insulate the rest of the country.

Another plus is that the vast majority of Africa’s population lives in the rural areas, which means less crowding and limited social interactions.

The other strength is that some African countries have some experience combating communicable diseases like Tuberculosis, HIV, Ebola, Rift Valley fever, among others.

This implies the tenacity and the flexibility to battle yet another addition to the family of communicable diseases within its existing infrastructure.

The stage that you live, you learn, seems to be working for Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. These three West African countries bore the brunt of the Ebola outbreak between 2014 and 2016. Informed by their past experience, they have been implementing some of the lessons like testing at entry points and contact tracing.

This level of déjà vu worked for Nigeria and Senegal when Ebola spread in these countries. They had had the benefit of time to see what had worked in the neighbouring countries.

They used the arsenal of lessons to halt the spread of Ebola through port of entry screening, fast and thorough tracing, monitoring of contacts, as well as rapid isolation.

The question to ask now is, would implementing universal health care have saved the continent from the troubles it is undergoing right now?

Universal health care is founded on a simple but critical principle that everyone receives quality health services without reference to their financial capability.

The singular consideration for service is that one receives treatment if they need it, whether they can afford it or not. The Sustainable Development Goals stipulate that by 2030, all regions will have universal health care.

We are 10 years away from the set deadline and there is coronavirus to remind us why having strong healthcare systems would have made this burden lighter. According to the CEO of Amref Health Africa, Dr Githinji Gitahi, ‘’Many countries have adopted the political declaration that was done at the UN General Assembly in September and agreed and signed to it. The talk has happened but the walk has not happened’’.

The fissures that exist in most of Africa’s healthcare infrastructure have come to bare in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. It’s now a last-minute effort to equip systems that were already under resourced.

In a BBC Africa Facebook Live, the Head of Africa World Economic Forum, Elsie Kanza, said, “We have already seen the negative effects in terms of healthcare as countries scramble to get facilities up to scratch. They were weak beforehand and now governments have to operate under a crisis mode to close those gaps.” Operating under pressure in the midst of a pandemic comes with its own added frustrations.

Africa shoulders one-third of the global disease burden and its health infrastructure is deficient by global measures, among them patient-doctor ratio. With a population of more than 1.3 billion people, most of the countries have an average of two doctors per 10,000 people. Nigeria, Africa’s most populated country, has a ratio of four doctors per 10,000 people; Kenya has two while the Democratic Republic of Congo has one, according to the WHO. The proposed WHO ratio is one doctor per 1,000 people.

Moreover, some of the continent’s healthcare systems have been propped up by donor funding. With the economic recession and contraction unfurling in Western Europe and North America, Africa will have to rely largely on its own resources in the future.

So far, there have been complaints about the quality of care for those in need of treatment, while healthcare workers lament they have not been adequately equipped to deal with a problem of COVID-19 magnitude.

Currently, there is apprehension that numbers of those infected will rise and the bed spaces, especially for those who require intensive care, might fall short.

The World Health Organisation estimates that there are less than 5,000 ICU beds available in 43 African countries. This translates to having five beds per one million people.

In some 41 countries, there are less than 2,000 ventilators available in public health facilities according to the WHO data. These numbers are going to change dramatically once the efforts by different countries to increase capacity are completed. There is also the donation made by the Chinese billionaire Jack Ma that has not been factored.

Ventilators are crucial for those who need critical care.

To be concluded

Mawathe is the Health Editor for BBC Africa’s Life Clinic

END

Be the first to comment