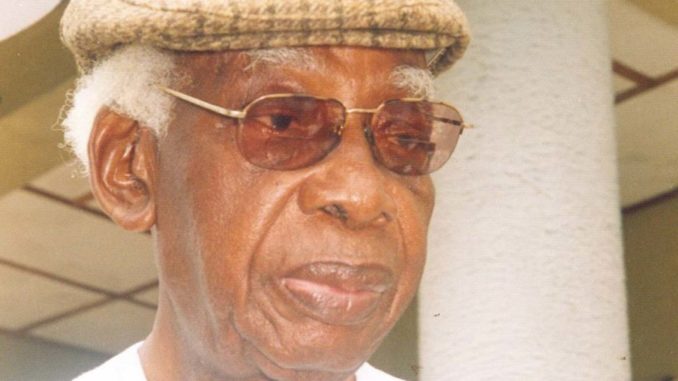

It is in the lyrical and simple depiction of the pristine environment and serenity of indigenous cultures and clime that we first appreciate the poetry and writings of poet-par-excellence, Gabriel Imomotimi Gbaingbain Okara who died on March 25, a few weeks short of his 98th birthday.

Long before the environment became an issue in world affairs, in his poetic oeuvres and poetic-prose narratives, Okara captured the idyllic life in the rural areas and how modernity had negatively impacted culture and humanity. His iconic novel, The Voice (1964) which epitomises the search for ‘it’, raised his stature as a philosopher-writer much in the tradition of the poet as an unacknowledged legislator, probing what becomes of the African when in contact with the overwhelming incursion of western and foreign values. In that novel, he did a literal translation of ijo language into English with all its associated inflexions and cultural nuances. But Okara was indeed acknowledged in his homeland and The Voice is considered in literary circles as a successful experiment.

Born in Bomoundi in 1921 in the Niger Delta, Okara had his education at Government College Umuahia and proceeded to Yaba Higher College Lagos. He then proceeded to the United Kingdom in search of the proverbial Golden Fleece. While abroad he attempted to join the British Royal Air Force but for some reason did not complete the pilot training. He worked for a while with the precursor of British Airways, the British Overseas Airway Corporation, improved his education and came back to the motherland.

Back in Nigeria, Okara began work with Government Press in 1945 and remained there for nine years working as a printer and bookbinder. It is on record that it was during this period that Okara began to write. He translated poetry from his native Ijo language into English and also did some scriptwriting for the radio. Along with other important writers such as Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, John Pepper Clark, Christopher Okigbo to mention but a few, Okara attended the June 1962 Makerere African Writers Conference in Kenya in which important pronouncements were made on the definition and future of African literature. In 1949, he went to the U.S. and studied journalism at Northwestern University. With this qualification, he worked as Information Officer in the then Eastern Nigeria Government Service. At the outbreak of the Nigerian Civil War in 1967, he along with fellow compatriot and writer Chinua Achebe served as ambassadors for the Biafran government in 1969. After the war he headed the Rivers State Publishing House from 1972 to 1980.

Okara lived and died as a writer right from his early days when he wrote plays and features for radio. His iconic poem The Call of the River Nun, a must-read for all West African School Certificate Examinations in the 1970s, won an award at the Nigerian Festival of Arts in 1953. Some of his early writings were also published in the literary magazine Black Orpheus. Piano and Drums perhaps the most famous of his poems captured the clash, which happens when two cultures meet. Other works such as You Laughed and Laughed, Once Upon a Time, Little Snake and Little Frog – for children, (1981), An Adventure to Juju Island- for children, (1992), The Dreamer, His Vision (2005) The Fisherman’s Invocation (1978) and As I See It (2006) forever carved and stamped his name on the literary canvas of African literature. It is reported that some of his manuscripts were lost during the 1967-1970 conflagration.

Okara won recognition very early in his career particularly among his colleagues and contemporaries. Apart from the Nigerian Festival of Arts award in 1953, in 1979 he won the Commonwealth Prize for Poetry with his entry The Fisherman’s Invocation. In 2005, he won the NLNG Prize with his entry The Dreamer, His Vision. The Pan African Writers’ Association gave him an Honorary Membership Award in 2009. The Gabriel Okara Literary Festival was held in the poet’s honour at the University of Port Harcourt in 2017 and later that year a book Gabriel Okara, edited by Chidi Maduka was published. One of the fine points made by Maduka was that the book established Okara’s stature “in African literature and the fact that he has not been given his full due in African literature.”

With the exit of another icon from the Nigerian literary space, the country has lost a father-figure and an arcane poetic master whose long lifespan straddled two centuries and the different cultural effusions of the period. His simple lifestyle and philosophical underpinnings are a study on how to live in a world largely propelled and determined by the power of the filthy lucre. Although he is gone in flesh, the spirit of the writings of Gabriel Okara will certainly outlive him. The federal and state governments should consider naming a legacy project after Okara considering the significance of his immense contribution to the arts while he lived. We are reminded that for all its insistence on and preference of the sciences, it is in the Arts that Nigeria has gained global attention through our worthy ambassadors of the pen.

Adieu, Gabriel Imomotimi Gbaingbain Okara till the resurrection!

END

Be the first to comment