Talking Points

—- Show me your hero and I will tell you who you are.

—- You know a country by the kind of people it remembers.

—- Nigeria’s unity is not negotiable because you cannot negotiate what does not (yet) exist.

—– Nigeria: Political re-structuring is not enough.

—– Adekunle Fajuyi was the first major Nigerian figure to achieve the proverbial handshake across the Niger.

—– Adekunle Fajuyi is Omoluabi in the true Yoruba sense of the word

—– Fajuyi died as a soldier. He lives on as an Idea.

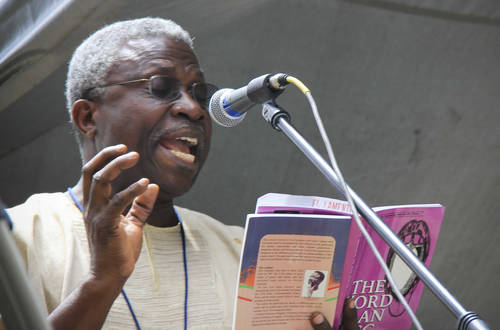

My participation in today’s event is prologued by a pleasant serendipity. When in March this year I received a telephone call from Engineer Francis Ojo, that wizard of nuts and bolts who also thrives as analytical thinker, passionate nationalist, political polemicist, and intrepid author of sizzling prose, I thought he had eavesdropped my conversation with a fellow Nigerian three days earlier about Lieutenant-Colonel Adekunle Fajuyi, the first military governor of Western Nigeria, and what a forgetful, ungrateful nation had done to the remembrance of his exceptional gallantry and inspiring integrity. But my earlier chat took place in the United States, while Mr. Ojo’s call came, three days later, from England. Therefore, there was no way our engineer could have overheard this chat across the vast Atlantic (no matter the degree of his engineering wizardry!). So I was immeasurably pleased to know that there were many of us in different parts of the world who just couldn’t forget this remarkable soldier-leader, and are bent on making sure that the country for which he sacrificed his life does not.

And when Mr. Ojo told me that the ubiquitous Yinka Odumakin was there with him (in faraway London) as he asked if I could deliver this year’s Fajuyi Lecture, I said to myself ‘Aaah, Yinka; there comes my July Nemesis again!’ For it was in July 2008 that Odumakin ambushed me for the MKO Abiola Lecture; four years later and in the same month (along with the irrepressible Pastor Tunde Bakare: bless his soul!) the Save Nigeria Group (SNG) Lecture; now, after another four years, and yet another July, the Fajuyi Lecture. What shall we expect in the seventh month of year 2020; and 2024?

But this year and this month have chosen themselves as those to remember. For, this month, this day, half a century ago, Nigeria experienced its second coup de tat and first counter-coup. A batch of gun-wielding mutineers, bent on evening out the ethnic scores of the gory murders perpetrated by Nigeria’s first coup, stormed the Western Region government house, Ibadan. Their prime target/quarry? General Aguiyi Ironsi, the then Head of State on a visit to the Western Region capital. But Adekunle Fajuyi, quintessential Omoluabi, refused either to surrender or abandon his guest. The gallant soldier went down with his Commander-in-Chief. In addition to this and several other acts of chivalry, Fajuyi’s six-month tenure as military governor marked him out as a man endowed with tremendous moral strength and exemplary leadership. What principles of Omoluabism undergirded Fajuyi’s thought and action? Why is this gallant soldier hardly ever remembered save in his ethnic base? What does this say about Nigeria’s imperfect union, the character of her values, the nature of her memory, the politics of her remembrance? These are some of the questions this lecture intends to address.

Of Heroism, Memory, and the Crises of Remembrance

In Galileo, one of his most thought-provoking plays, Bertolt Brecht, the prodigiously inventive German playwright, poet, polemicist, and humanist, jolts our rational faculty with his now famous confounding adage: ‘Unhappy the land that is in need of heroes’. Like most of his epigrammatic interventions, this one too functions like a double-edged sword, pitilessly sharp on both edges, sounding both as a settled truism and contestable verity. The more we try to unravel this saying, the more it riddles itself into further complication:

1) Why should the land be ‘unhappy’ because it is ‘in need’ of heroes? Could it be that that land has no heroes because it is so uniformly mediocre, so inveterately ordinary, so universally depraved that it is incapable of producing that caliber of persons who tower above time, place, and circumstance, whose temper constitutes the template for enviable conduct, whose significance, therefore, is deeply felt, widely acknowledged, and vitally desirable? A land with a positive answer to this beguiling question could be said of be afflicted with what I have decided to call the Hero Deficit Complex (HDC), a land with a missing ace in its grid of values.

2) Is the land ‘in need’ of heroes because it cannot function optimally (even minimally) without the tutelage and overarching dominance of this club of superior humans? This poser resolves itself into other questions: when does the hero transmogrify into a crutch for a disabled society; the pillar for their falling edifice? How ‘equal’ can a people be who draw their strength, sustenance, even raison detre, from those that are more equal? Can the hero really stand so tall without the genuflection of the hero-worshippers? To put it another way, the inevitability quotient of the hero invariably creates its own Hero Dependency Complex (HDC)

Let’s simplify our submission so far into two direct declarative sentences: That land is unhappy which is incapable of producing heroes; that land is also unhappy which is always or forever dependent upon heroes.

Despite these two premises – or because of them – the concept and practice of heroism persists in every human society, and countless societal institutions have collaborated in ensuring its persistence. And as Wale Adebanwi has persuasively demonstrated (Adebanwi 2008), in Yorubaland, heroism, and ancestor worship are mutually reinforcing, mutually perpetuating phenomena. And in this regard, the dividing line between god and man, the celestial and the terrestrial, the sacred and the profane is remarkably thin, as most supernatural Yoruba notables migrate between the two states of being with existential ease: Ogun was a hunter/farmer before his elevation to the divinity in charge of iron and metallurgy; Sango moved from mortal royalty to divine ascendance; while Osun, Oya progressed from our workaday corporeal existence to goddessly transcendence. But the journey from human to divine is never a common, routine transition. It has to be earned through the achievement of monumental feats and the cultivation of superhuman accretions. And, in many cases, the extraordinary quality of the life lived must be complemented by the unique nature of the death experienced. For the person marked out for deification must be somebody capable of commanding both adoration and emulation (our vertical gaze) without demanding them; a Titan worth every syllable in the panegyric which extols his worth.

Living heroes are powerful; those dead are doubly so, because though dead, they are never gone. On the contrary, they are believed to have merely transited to the realm of ancestorhood, that zone of reverential omniscience and respectability, of unvarnished verities and settled wisdom, beyond the giddy hustles and petty bickerings of sublunary existence. Which is why in an apparent mix of necromancy and cultic invocation, the present is constantly in dialogue with the past; the verbal structure of societal communication is characterized by a tense and aspect protocol that defies the logic of quotidian time. Greek memory glows with the Golden Age of Pericles; the Russians are gratefully aware that the epithet ‘great’ in ‘Peter the Great’ is true and valid to its last letter; the English know when to invoke a Chaucer or a Churchill; hardly one day passes in Turkey without some reverential mention of Ataturk; at Rushmore, the United States hew out of a granite rock four faces of those she considered the most pivotal of its Presidents in 0ver 200 years; the brave island of Cuba, Fidel Castro is a stanza in every song. In a most conspicuous spot in Ljubljana, the beautiful capital of Slovenia is a huge statue of France Preseren, patriot and patron saint of Slovenian verse whose lyric throbs in the air each time the Slovenian anthem is sung. And coming closer home, how can we sing Africa’s Freedom song without giving the wind the names of Nehanda, Samoure Toureh, Lumumba, Nkrumah, Mandela, Mandela, Mandela, Mandela?

Not all ancestors are heroes. Nor are all heroes ancestors. A hardly surprising observation, considering the fact that while ancestorhood is assumed/ascribed more or less like a milestone station in a rite of passage, something akin to an inherited status, heroism is earned/achieved invariably through arduous trials and extraordinary accomplishments. But these two brands of beings are obligated to one recalcitrant phenomenon: Memory, the antidote to oblivion, that lingering resonance of the music of fame. Memory is a large meandering river; History is its fountainhead; names are its index markers; memorabilia and other icons of forget-me-nots are the boulders in its fluid and fabulous fare. Remembrance is its active and vital current. For, Memory without Remembrance is like tinder without a match; a tiger without its leap. To remember is to spring into life, to call dormant thoughts, passive ideas, somnolent sensations into active service; to bring the past to bear on the present and fling a bridge between it and the future.

Human life is fickle, finite; it is Memory which roots it to a certain stability and significance through its (Memory’s) dominion in the collective consciousness and the deep structure of the syntax of being. It is Remembrance which constantly calls it forth and up to the surface, making sure it does not end up like that priceless garment which spends all its life in the locked-up wardrobe. Memory is action potential; Remembrance is action actual. To a great extent, Memory approximates the state of Being; Remembrance the process of Becoming. Memory is the giant eagle at the bottom of the Iroko; Remembrance is the wing which gets it to its coveted place on the tallest branch. If Memory is the temple, Remembrance is the priest who airs its ardent supplications.

Because Memory is so silent and Remembrance such a rare virtue, we strive to cheat Oblivion with statues, plaques, sculptures, paintings, myths, and tendentious facts. We inscribe eloquent epitaphs on the grave of the silent dead and humour their hubris with defiant elegies. But statues tumble; epitaphs fade; elegies go stale. Like their human subjects, reputations wax and wane, wane and wax. Social death frequently completes the rout begun by biological death. Some reputations glow like burnished gold across the ages; others rust like pitiable lead. Memory management has become a lucrative business in contemporary times (consider the frantic traffic in commemorations, dedications, citations and sundry souvenirs, and the ease with which the art of biography writing has degenerated into the scheme of hagiography peddling in contemporary Nigeria), but remembrance is much more difficult to control much less manipulate. So while memory is residual, non-obtrusive, remembrance is more deliberative, more energetic, much more amenable to personal drive and the will to recall.

But in the last analysis, there comes a point at which a hard and fast distinction between these two faculties becomes academic, even frustratingly pedantic. For the two can hardly do without each other. Remembrance needs a memory bank to draw upon; while memory can hardly do without the currency and disseminating agency of memory. To put it in the simplest terms, there cannot remembrance without memory; at the same time, memory without remembrance is like a ton of gold locked away in a dark, un-accessed vault. One of our problems in Nigeria is the low premium we place on memory, and our dangerous inability – and unwillingness – to remember. Col Adekunle Fajuyi, the eminent subject of this lecture, is a prime victim of this malaise. But more on that later. . . .

Show me your hero….

You know a country by the kind of people it chooses to celebrate and valorize; you also know it by the kind it seeks to denounce and denigrate. Additionally, you know a country by the caliber of people it seeks to remember, and the type it is anxious to forget. Show me your hero and I will tell you who you are. Because in Nigeria our memory is so scanty and skewed, we do not only remember differently; much more frightfully, we remember defectively. Our public spaces are filled with images of patent criminals; our musicians pollute the wind with praise songs for sundry scoundrels with obscenely deep pockets; countless associations mushroom (especially in our institutions of higher learning) peddling all manner of ‘prizes and awards’ to moneyed crooks on a shamefully cash-and-carry basis. The Federal Republic of Nigeria sanctions this gross devaluation of worth/integrity by the way it doles out its ‘national honours’ to recipients many of whom are notorious treasury looters, election riggers and suchlike political jobbers, economic saboteurs such as the ‘round-trip’ pilgrims of the banking sector and the phantom oil-subsidy mafia, the ‘exporters, importers, and manufacturer’s representatives’ of a nation without factories. . . . . .A bizarre logic rules the purpose of the Nigerian national honours roll: the more heinous your crime against the nation, the higher the rank of your award, the more glittering your medal, the firmer the presidential handshake . . . .

So, those widely known to the people as abominable villains are decorated as national heroes. Those who should be rotting away in jail for crimes against the people are treated like ardent patriots and showered with accolades. A damned natural process, you would be right to say, in a vicious kleptocracy parading the mask of a decent democracy. Nigeria is a country with no set of positive values, a place where virtue is punished and vice is rewarded, a nation with a dwindling reservoir of positive models and mentors.

The foregoing issues were not far from the top of my mind throughout the composition of the poems in Early Birds, my three-volume book of poems for Junior Secondary. When in 2001 Chief Joop Brekhout, then owner of Spectrum Books, Ibadan, floated the idea about the necessity of appropriate poems to cater to the literary and cultural needs of students in the Junior secondary cadre, and his editorial team embraced the suggestion with contagious enthusiasm, hardly did they know they were tapping into a fervent desire I had nursed for years – to enter into dialogue with the minds of young folks through the medium of poetry, and get them to know that juvenile verse has a purpose and province richer, more socially engaging than those offered by the ‘Twinkle twinkle little star’ variety. The poems in the three volumes covered all the essential topics and themes of poems for young readers, but they never came without a bit of ‘civics lesson’, for I have always believed that it is part of the function of poetry to show young people the world and where they stand in that world. For, for the poem to be holistically beautiful, it also has to be useful.

So, in addition to so many matters of cultural and social significance, I made sure each volume ended with poems on notable Africans: Tai Solarin, Mabel Segun, Gabriel Okara, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Nelson Mandela, men and women of grace and gravitas whose lives and ideas I consider both admirable and emulatable. When the manuscripts were in, a member of the editorial board wondered what such ‘heavy’ names were doing in books for children. My response: my intended readers are old enough to discern their heroes and choose their models, and I saw no sin in creating poems which pointed them in the right direction. Besides, no poem is innocent, not even the most naïve of nursery rhymes. Humpty Dumpty may spring a humbug, depending on how it is read, and by whom and to whom. I have always believed that singing and learning are not mutually exclusive activities in matters relating with lyrical verse.

Nigeria’s Heroes’ square is crowded with anti-heroes, and Nigerians need to know there are many, many positive alternatives to the crooks and scoundrels who dominate the country’s socio-economic and political space and poison the well of its values. Call it ‘Catching them young’ or showing them the way, this literary evangelism is powered by my belief that the songs we sing in our childhood days end up shaping the way we think in our adult years.

Fajuyi, Omo Ayiye, Omoluabi

Were Nigeria a country with a solvent memory bank and an faculty of active remembrance, Adekunle Fajuyi would have his statue in prominent public spaces all over the country, and the story of his gallantry told and retold from generation to generation. For when those mutineers assailed the government house in Ibadan on the night of July 29, 1966, and demanded the head of his guest, General Aguiyi-Ironsi, Nigeria’s head of state, Fajuyi, in the true spirit of Omoluabism, refused to betray his Commander-in-Chief who was also his guest. He stood his ground. He barred the exit of honour from his household with his own body, with his own life. It is worth noting that even in those urgent and mortal moments, Fajuyi had a choice. He could have cut and run. He could have reached for the typical Nigerian option by trading the security of his guest for his own safety and possibly some plum position in the new government that was sure to emerge from the coup. Had he struck this deal and surrendered his guest, he would have triggered a development with far-reaching personal, ethnic, and national repercussions. Perhaps that decision would also have changed the course of Nigerian history and its ethno-regional complexion as we know them today. But he stood his ground. He chose the path of honour. Over my dead body, he said, and the mutineers took him for his word. It takes one akoni (somebody with exceptional courage and valour) to recognize those virtues in another. This is how Akoni Wole Soyinka remembers the fallen hero:

Honour late restored, early ventured to a trial

Of Death’s devising. Flare too rare

Too brief chivalric steel

Redeem us living, springs the lock of Time’s denial

(Idanre and Other Poems, p.54)

Noteworthy in this piece of verse is the way the key words re-arrange themselves into a new collocation of attribution: the soldier-leader with ‘rare’ ‘flare’ and ‘chivalric steel’ who ‘redeem[ed]’ us by getting our ‘honour’ ‘restored’ but who, unfortunately, fell prey to ‘Death’s devising’. These are words which pay homage to the gravitas of Fajuyi’s historic assignment as well as the resonance of his noble personality. The latter parts of the poem deepen our admiration for a truly remarkable leader who conquered fear and the ‘dearth of wills’; this latent tree from which ‘soared a miracle of boughs’. Fajuyi died like a man; now he lives like an Idea.

The events of the night of July 29 have generated different narratives, and the Fajuyi phenomenon has lengthened into a yarn over the past 50 years, with all manner of fictive recreations and mythic accretions, partisan inflation and revisionist adumbrations. Just as well: the hard copy of martyrdom hardly ever comes without the malleable software of myth and fabulation. But for a closer look at the man without/beyond the myth, we must pay more than a cursory attention to those few but profoundly revealing pages in The Man Died, detailing Wole Soyinka’s one-on-one encounters with Fajuyi the soldier and Fajuyi the man… ..

Fajuyi and Soyinka: two men of exceptional import, without a doubt: courageous, clear-headed, visionary, humane; one the first military governor of the old Western Region, the other Africa’s leading dramatist and one of the pillars of its political conscience. In just 18 pages (pp. 144-162), we learn so much about the mind and character of this 44- year soldier with the historic task of pacifying the Wild, Wild West and cleaning up the bloody mayhem precipitated by months of rampant anomie occasioned by the blatant rigging of the October 1965 elections by the tyrannical Nigerian National Democratic Party, NNDP (frightfully and derisively referred to as ‘Demo’).

In these few pages, we see Fajuyi’s consternation and anger at depraved public officials who want to hang on to office by all means even ‘when their usefulness is over’ (p. 148), and ‘The honourable course is to resign’ (p.147). An achingly sad example is the discredited former Chief Justice of the then Western Region who came begging to retain his position:

But do you know what the man did? He went on his knees, there, right there, an old man like that, a whole Chief Justice, he went down on his knees and began begging me. I was angry. I shouted on him to get up but he wouldn’t; he kept on saying, ‘I beg you sir’. So I walked out. When I felt he should have recovered himself I sent the guard to go and tell him to leave (p.147).

Evident, even audible here is the moral outrage of a leader with a cleansing mission, a deeply conscientious crusader strongly appalled by evil. And this moral crusader knew all too well that the crusade had to start with himself. Days later, when Soyinka told him somewhat accusingly ‘I saw you arriving at a function in a Rolls Royce. . .’, Fajuyi’s response was forthright, even apologetic:

Ah, I know what you are about to say, and I’ll admit that I didn’t like it either. But there was nothing I could do at the time. We were nearly late and those security men had already allocated the car for me. I was more or less pushed into it. But I agree with you entirely. It’s disgraceful that we soldiers should take over the ostentation of those useless politicians. (p. 153). (My emphasis)

Thereupon the Governor scaled down his automobile choice to a Mercedes. And even then, he promised to paint that car in military colours. And he did! Still more from the gallant soldier:

As for the rest of the cars I’ll put them up for sale. The Cadillacs, the Rolls, all the submarines. The government could use the revenue. (p. 253).

After reading this, you just cannot doubt that a virtue called Accountability once had a prominent place in Nigerian governance. Fajuyi agonized over the incipient streak of materialism among his colleagues, as evident in some of the top officers’ scramble for Crown Lands. He was soon tagged ‘radical’ and a certain chill, even distrust, descended on the warm relationship between him and his somewhat pro-establishment Commander-in-Chief. When Soyinka asked for his opinion about Ironsi’s decision to rotate the governors, Fajuyi responded with an astounding mix of premonition and prophecy:

To tell the truth I am not too happy about it. I would like to finish what we’ve begun. I mean, we’ve hardly started! Still, I always remind myself of what I criticize in others – nobody ever wants to leave. I am beginning to fear that the army itself may not know when it is time to go (p.159). (My emphasis)

To think that the fear so clairvoyantly expressed by Fajuyi here in 1966 came to be so painfully justified about a quarter-century later in the diabolic despotism of the billionaire Generals and military politicians! There goes Lt. Col. Adekunle Fajuyi, veritable Officer and Gentleman, a soldier who sought the company of intellectuals and in whose company they felt at home and at ease. Earnest, forthright, sensitive, and mentally and emotionally astute, Fajuyi combined the moral energy of a reformer with the sizzling idealism of a committed intellectual. He possessed anger and compassion, chivalry and vulnerability in the right proportions.

Though invested with a tempting combination of military power and political authority, he did not wield the sword like a blind samurai; he never forgot the right ways of being human. There goes a warrior beyond the common run of contemporary Nigerian soldiery. For when you compare the likes of Fajuyi with the scheming, thieving, avaricious, and utterly dishonourable soldiers of fortune who puff around in our military uniforms today, you are compelled to ask: where are all the good men gone? Professor Bolaji Akinyemi (2001) intended no hyperbole, therefore, when he extoled Adekunle Fajuyi as ‘the only hero the Nigerian army had ever produced’.

From July 29 to June 12 – and Beyond

But why does the pendulum of this gem of a soldier-leader swing between deification and oblivion? Why does it take so much stress, so much strain to commemorate this hero whose remembrance we all should find as natural as the way we breathe? Again, the political economy of Memory and the fiendish vicissitude of Remembrance. The outpouring of feelings and tributes which accompanied Fajuyi’s assassination in 1966 and burial in January the year after thinned out after a few months as the country moved on to other crises: the pogrom on the Igbo, the rise of Biafra, the civil war, the inconclusive end of the war with its hypocritical ’No Victor, No Vanquished’ slogan, and the apparently endless cycle of coups and counter-coups with all kinds of military adventurers at the helm. A long, gruesome campaign for democracy forced the military to organize the presidential polls of June 12, 1993. Against all odds, and quite contrary to the wildest expectations of the military, that election produced a clear winner. The crown was about to land on the head of that winner when General Ibrahim Babangida’s military junta stopped the music and threw the country into a tailspin.

The undeclared winner of that election, Chief M.K.O. Abiola, insisted on his mandate. Disgraced out of power, General Babangida passed on the baton to a feckless Interim Government which soon collapsed under the weight of its own illegitimacy. Then came General Sani Abacha, maximum dictator, kleptocrat, and murderer who killed those democracy advocates he could lay his hands on and hounded the others into painful exile. Rather than see the annulment of the June 12 election as a rape of democracy and assault on our national will, many Nigerians soon naturalized it as a Yoruba problem. M.K.O. Abiola’s nation-wide mandate was driven into a tribal enclave. But NADECO and a body of other Civil Rights groups pressed on for the demand for democracy. Unfortunately, Chief Abiola never saw democracy when it came at last, having collapsed and died after that mysterious cup of tea offered him in captivity, during (we must never forget) General Abdulsalaam Abubakar’s tenure as Head of State.

The June 12 ‘debacle’ (a word deployed and made irresistibly popular by Nigeria’s foremost journalist, Olatunji Dare) brought to the fore once again, the Yoruba Factor in Nigerian politics. Under frequent assault by Abacha’s killer squads, left on their own by other Nigerian ‘nations’, the Yoruba started examining their own room in the Nigerian house. Slogans such as ‘Confederation is the answer’ flared up on prominent pages of newspapers (The last time that statement appeared with that kind of spectacular prominence was 1983, in the aftermath of the grossly rigged federal elections); ‘The National Question’, ‘Sovereign National Conference’, ‘True Federalism,’, ‘Self Determination’, etc. Not a few people started contemplating the idea of ‘Oduduwa Republic’. But most telling was the way the evocation of Yoruba ‘heroes’ came to be endowed with a prominent role in this ritual of ethnic self-validation and the retrieval of communal self-worth. Abiola, martyr of democracy, found a worthy predecessor in Adekunle Fajuyi: both being icons of gallantry and extraordinary sacrifice whose light shone beyond their ethnic base; Chief Obafemi Awolowo, unarguably the architect of Yoruba modernism whose place/stature in Yoruba mythology is only next to that of Oduduwa, the group’s primogenitorial avatar. At work here is what Wale Adebanwi has aptly delineated as the ‘political and cultural uses of memory’ (p.433); that is, the power of collective memory, through the instrumentality of remembrance, to bolster the communal psyche, salve and restore a wounded pride.

Yes, indeed, we know a country by the kind of people it chooses to remember; we also know it by the kind of people it fails, or chooses, not to remember. If Nigeria were a country with a sense of history, Col. Adekunle Fajuyi would be a prominent member of those ‘heroes past’ it crows so lustily about in its national anthem. But this ‘gathering of the tribes’ (Soyinka’s phenomenally prophetic phrasing in A Dance of the Forests, a play that was intended, most ironically, as a celebration of the country’s independence in 1960, but which ended up as a chilling disquisition on its imperfect union!) still totters on from error to error, with the possibility of genuine nationhood as a distant hope. The virus of this pathology of being has compromised the necessary health of becoming, as tribal (I am using that epithet in full cognizance of its pejorative anthropological accretions!) considerations continue to trump national imperatives, and a dreadful vice on the national stage may be an enviable virtue at the tribal level. The likes of Adekunle Fajuyi are not recognized as national heroes because there is as yet no ‘nation’ to be a hero in or of.

This is why the National Question in Nigeria is perennially in search of a National Answer as ethno-regional loyalties ossify into deafening walls, and each group is fixated on its own survival most times at the risk of the national collective. No country can ever achieve nationhood when its component parts are as incorrigibly heterogeneous and so mutually antagonistic as Nigeria now is and has always been. This is why those who blissfully aver that ‘Nigeria’s unity is not negotiable’ should quickly reconsider the dangerously complacent certitude in their avowal. This was one of the cheesy slogans which propelled the rhetoric of the Nigerian civil war, and it rode to victory in a crass, largely un-interrogated cavalry. But that was in another century, another millennium, another ideological ferment, long before Benedict Anderson’s idea of the Nation as an ‘imagined’ community, and the nation itself as a shiftable, shifting arrangement/artifice with its own unfair share of the profound indeterminacy that is so indigenous to the postmodernist/poststructuralist condition. Besides, those who talk so glibly about ‘Nigeria’s unity’ are under the perilous impression that there is a ‘unity’ to ‘negotiate’, in the first place. But a closer look tells us that we are still a thousand miles and a thousand moons from that unity, and that we need to work really hard and honestly for it to come within our grasp. General Alani Akinrinade said this (and much more) when he declared with authoritative candour in last Sunday’s Guardian: ’There is nothing like unity in this country’ (p.15). Closely related to this viewpoint are Professor Banji Akintoye’s numerous writings about the National Question, particularly his recent interventions in The Nation (July 14, July 21). Let’s tilt our ears in the learned griot’s direction:

There is no country on earth that is beyond being dismembered or dissolved. Throughout human history, countries have arisen, flourished, and then lost some parts, or broken apart. (The Nation, p. 19)

Some of the eminent scholar’s views on this matter are decidedly controversial, and many readers might be constrained to see Professor Akintoye’s statements from the prism of his passionate Yoruba nationalism, but the intellectual sagacity and sheer un-ignorable force behind the historical antecedents which inform his submissions make them so compelling for those interested in a genuine discussion of Nigeria’s National Question. Time to hold the bull by the horns; you do not solve a problem by wishing it away, or by denying its conspicuous existence.

As yet, Nigeria has no ‘unity’ to negotiate or not to negotiate. Which is why President Muhammadu Buhari must not only read the reports of the 2015 National Confab; he owes himself and the country a critical duty to read, digest, deliberate on, and identify its implementable parts- beyond all partisan and ethno-regional considerations. To wave off the lingering call for a re-structuring of this country is to risk the possibility of suicide through denial. Fredrick Lugard’s expedient contraption has been aching in every joint since 1914. If the house has not fallen according to Karl Maeier’s apocalyptic prognostication, it is simply because Nigeria has been extraordinarily lucky. The Avenging Angels of the Niger Delta, the resurgent Biafra agitators, the increasingly violent clashes between nomadic herdsmen and native populations, and other ethno-regional and religious eruptions in different parts of Nigeria are all pointers to the cracks in the walls of the house that Lugard built for the glory of the British Empire. The component parts have never met on any genuinely democratic platform to negotiate the terms of their co-existence. We cannot afford not to do something about this imperfect union. To refuse to re-structure is to prepare to de-structure.

But there is a vital need to scrutinize the word ‘restructure’ and interrogate its promiscuous connotations in our current political lexicon. For that term has become a mantra, a miracle code, and sound bite in the mouths of political opportunists, and some vengeful incantation in the arsenal of those temporarily out of power – but trying to scheme their way back to it. In other words, the Nigerian union is perfect if you are in the saddle, and out of joint only when you are out of control. Besides, the ‘re-structuring’ we need must go beyond the surface structure of the polity and reach far into the deep structure of the economy. For it is absolutely impossible to establish any political stability on the foundation of the present consumptive, prebendal, and pathologically unproductive economy with its suicidal dependency on oil. Is anyone talking about the moral structure of a country with a few bloated billionaires and millions of impoverished, disarticulated people? The way things stand today, every corner of Nigeria is a potential den of hungry Avengers.

The Yoruba strand of the National Question narrative deserves a thorough, hard-nosed, and visionary appraisal. Those who call for a relative autonomy that would allow Nigeria’s federating units appreciable room to develop their own way have their fingers right on top of the problem. For that, indeed, is the substance, soul and spirit of true federalism. But we need to find a way of doing this without allowing it to degenerate into a good-we vs bad-they; civilized-we vs primitive-they; advanced-we vs backward-they Manichaeism that ends up trumpeting the false superiority of one ethnic group and the assumed inferiority of the other(s). In other words, we must make sure that our ‘Yoruba Agenda’ does not bottom out as ‘Yoruba Exceptionalism’ with its attendant triumphalist provincialism and hubristic extremisms. For the separate ‘Yoruba Nation’ that is being canvased in certain quarters can never hope to be a nation of Angels. In other words, there is hardly any virtue or vice in the larger Nigerian body politic that is not in the Yoruba part of it. Much like other ethnic ‘nations’ in Nigeria’s ‘multi-national’ arrangement, the Yoruba have their own fair share of virtuous nation-builders and vicious nation-wreckers, consummate democrats and unrepentant ballot-riggers, conscientious citizens and conscienceless cesspools of corruption.

Furthermore, we must never underestimate the inevitable perils of homogeneity, the debilitating sameness in the cultural and socio-political gene pool that often breeds one-party states and their attendant despotic life presidencies, the kind of sameness that precipitated Somalia’s implosion prior to its eventual explosion. Forgive my skepticism as you consider this poser: if we cannot make Nigeria work together, is there any guarantee that we could make it work apart/in parts? The poet who sings an ode to diversity and difference couldn’t have chosen her/his Muse more judiciously. The avid Snooper Tatalo Alamu sums it all up so cogently with this characteristically brilliant remarks:

President Buhari needs not to be afraid of restructuring, but he should be wary of those who use the slogan of restructuring to preach hate and the summary dismemberment of the country. He should also be mindful of those who scream against restructuring as a strategy of keeping the nation in fossilized underdevelopment and Stone Age depredations simply to perpetuate an unjust system and its entrenched privileges. (The Nation, p.3)

Without a shred of doubt, there is so much in the life and legacy of Adekunle Fajuyi, the great man whose memory we celebrate, that speaks to the inward-rooted, outward-looking philosophy, the plural, tolerant, accommodating Omoluabism that is the core and guiding principle of Yoruba culture and science of being; that amplitude of spirit, that unstinting magnanimity that has always lifted our gaze beyond the parapets of jingoism and ethnic chauvinism. These are the virtues that have seen us through the turbulent upheavals of the past; they are the sure path to our ability to survive – and thrive – in the future. We are celebrating a Yoruba man who chose to go down with his guest and Commander-in-Chief who was Igbo, a true leader who saw office as service, who regarded the entire country as his political and moral constituency. A man so proud to be Yoruba yet so proud to be something more than, something beyond, that. We remember him well when and if we keep his enlightened, ecumenical spirit in focus, this man who placed such vital premium on loyalty and integrity, this man who taught us all a new way of being human.

The Road to Lalupon (seven hearty cheers to the authors of that title and its touchingly polysemic evocation!) is still long and snared, its palm trees pock-marked by the bullets of the mutineers of an unstable polity, the green leaves still droop with the blood of akoni ogun (brave warrior); the wind is still astir with the mad music of the gun. And there are still big questions begging for answers: is Lalupon a little comma in the sentence of our national discourse? Is it a terminus or a starting point; a cardinal spot or mere stop-over on our mapless search for nationhood? Is it a theatre or a temple, a well-paved path or a thorn-benighted crossroads? Whatever the answer may be, from Ado Ekiti to Lalupon is, no doubt, a fateful distance. From the heroic sacrifice of a long-gone Akikanju to the monstrous sacrilege of contemporary moral cretins, a long insufferably disturbing stretch. Once there was a soldier; now we are saddled with cannibalistically corrupt mercenaries in military uniform. The incomparable Fajuyi must be wincing in his grave today.

Yes, indeed, you know a country by the kind of people it remembers; you also know a country by the kind of people it chooses not to remember. Remembrance is an enabling companion of Memory; and also its handmaiden. So there goes Col. Adekunle Fajuyi, the soldier-leader for whom valour was a prime virtue, brave in battle, brave beyond it; paragon and parable. First true Nigerian to attempt that proverbial handshake across the Niger – with his own life. But so far, Nigeria has shunned that handshake, forcing that generous, idealistic hand to coil back to its startled pocket. Yes, were Nigeria a nation, the likes of Fajuyi would have their statues in every state capital in the country. But Nigeria is not yet a nation, not even a country if by that we mean an organized, coherent entity with mutually respecting parts bound by a set of identifiable (positive) values. Omoluabi Adekunle Fajuyi lived for that dream. It was for its sake he gave his life. His dream challenges our despair; his idealism upbraids the crass ordinariness of our leap of faith. We owe this great man a memory unencumbered by petty politics; a remembrance beyond the strictures of tongue and tribe.

I thank the Think Tank of the Association of Yoruba Professionals (Egbe Majeobaje), Egbe Majeagbagbe) for inviting me to deliver this lecture; for making sure we do not forget.

I thank you all for listening.

Ibadan, Nigeria Niyi Osundare

July 26, 2016

*I gratefully acknowledge Professor Wale Adebanwi’s assistance with the provision of research sources for this lecture much as I appreciate his seminal ideas on the cardinal issues.

Guest Lecture at the 50 YEARS AFTER FAJUYI Celebration, organized by the Yoruba Think-Tank; July 29, 2016; International Conference Centre, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

END

Be the first to comment