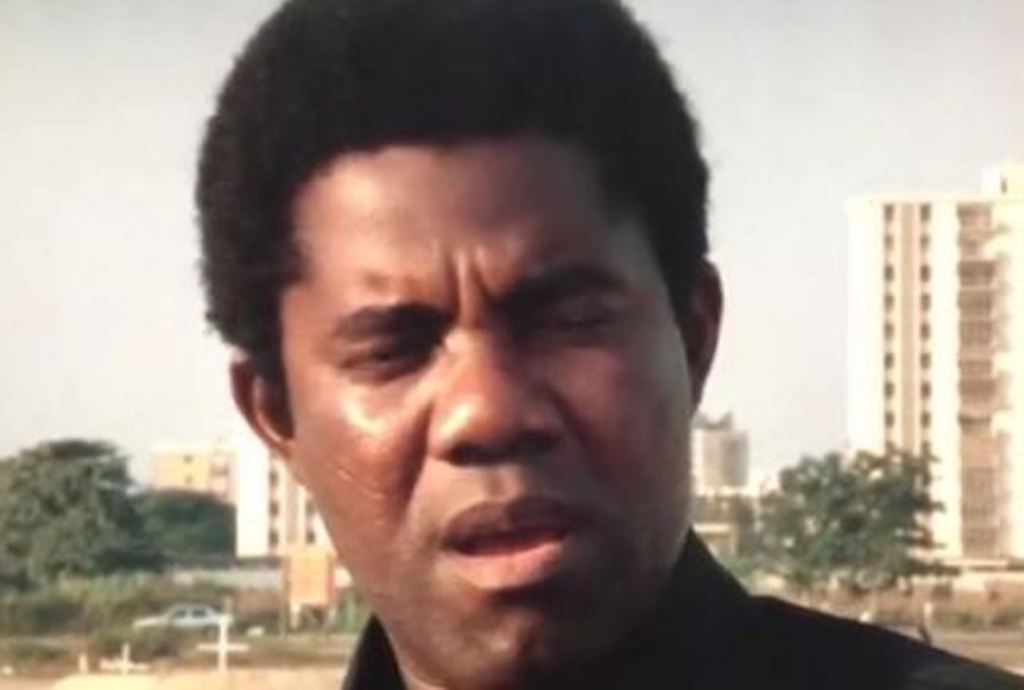

Physically attractive—a preternatural leading man—talented, hardworking and hardnosed, Afolayan had his break with the film Ajani Ogun, directed by Ola Balogun, in 1977. It was perhaps the first commercially successful Nigerian film.

In the last week of December 2016, members of the family of the late actor and producer, Adeyemi Afolayan (Ade Love), as well as the artistic community at large set about commemorating the twentieth anniversary of the death of this major figure in the history of Nigerian cinema. As I write, posts from Facebook, Instagram and Twitter appear on the word processor to announce the progress of the pilgrims to Agbamu, the filmmaker’s hometown in Kwara State. Oh, there on Twitter is a picture of party guests, and I can identify directors Tunde Kelani and Niji Akanni in a group decked out in aso ebi waxed with the commemorative image of Ade Love.

Theatres across Lagos have also been screening Kadara (1981) and Taxi Driver (1983), two of Afolayan’s films, in their original 35mm versions, according to information by Kunle Afolayan, the artist’s son, who is now a world-famous filmmaker in his own right. It may all sound like yet another instance of the periodic “flashes of memory” of which Nigerians, so well disposed to parties and festivities, are enamoured, but there is a lot to recommend in a weeklong memorial in honour of the distinguished showman.

Afolayan died on December 30, 1996, of complications arising from stroke. I still remember hearing the report over the radio while visiting Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife; the broken, perplexed, and mournful voice of the theatre practitioner Oyin Adejobi expressing deep shock at the news: Afolayan had recently visited him in Osogbo, and on departing had said something about leaving the older man in the hands of Jesus. Adejobi’s death came three and a half years later, in June 2000.

In a sense, Afolayan’s death in 1996, and Adejobi’s soon after, marked the symbolic demise of a tradition of Yoruba theatrical practice—the traveling theatre idiom. Hubert Ogunde and Ishola Ogunsola bowed out earlier in the decade. Anthropologist Karin Barber’s The Generation of Plays, published in the year of Adejobi’s passing, provides an excellent account of this practice, complementing Biodun Jeyifo’s earlier, kaleidoscopic study. (The collaboration between director-cinematographer Tunde Kelani and producer Alhaji Kareem Adepoju which resulted in the classic Ti Oluwa Nile (The Land Belongs to God, 1993-1995) can now be seen as the successful transition of that dying order into something more lively, pragmatic, and economically viable, considering the prevalent social orientation in the culture sector. Adepoju was the manager of Oyin Adejobi’s troupe and, with Kelani, he pulled off an integration of the old and the new in narrative and cinematic terms. Not a novice himself, Kelani was into his second decade as a filmmaker, and his career was being forged in a seamless traversal of different media—theatre, television, film.)

Afolayan was definitely more invested in the tradition about to be transformed. Although he attempted a home video film symbolically titled B’aye Ti Gba (Moving with the Times) in the mid-1990s, his heart wasn’t really in it, and I doubt that it found its way to the National Theatre. His films from the 1980s, particularly Taxi Driver and Ija Orogun marked the height of his career.

Physically attractive—a preternatural leading man—talented, hardworking and hardnosed, Afolayan had his break with the film Ajani Ogun, directed by Ola Balogun, in 1977. It was perhaps the first commercially successful Nigerian film. Interviewed in Ferid Boughedir’s Camera d’Afrique, a 1987 documentary about the development of African cinema, Balogun attributed the success to the incredible response of Nigerian—Yoruba—audiences which invaded the theatres at the sight of something totally new. The kind of entertainment cinema provided was more visually arresting than the physical encounter of live theatre. It gave performances a magical quality, and it appeared larger-than-life to eyes trained on the rectangular perspective of the television.

He made other kinds of great art. At least four of his children are prominent figures in Nollywood, the most storied being Kunle, director of highly regarded works such as The Figurine, Phone Swap, and The CEO.

The film also inaugurated Balogun’s productive collaboration with the traveling theatre practitioners, and can be viewed as the precursor to Kelani’s work from the 1990s. He subsequently directed Ija Ominira, another film with Afolayan in the lead, then Ogunde’s Aye (1980) and Moses Adejumo’s Orun Mooru (1982).

It was a short-lived relationship, however. The ingrained competitiveness of theatre artists soon kicked in, and every troupe leader began to fancy himself a cinéaste. The gifted, well-trained director was abandoned, or he did the abandoning. Barring a few exceptions (the films of Ladi Ladebo, the Adesanya brothers, Bankole Bello, Adamu Halilu, and Eddie Ugbomah), Nigerian cinema became little more than the coarse, exorbitant suturing of several situational narrations, heavy on dialogue and histrionics, and invested in supernatural themes. It favoured the kind of actor-focused approach to directing which worked in theatre but was ill-suited to cinema. Here came what the film scholar, Frank Ukadike calls “filmed theatre,” with some justification. Though successful in commercial terms, the experiment didn’t stand on sure grounds and it fell hard as a combination of economic and political volatilities turned the performing arts into a victim of structural adjustment.

Speaking to me in 2002, Balogun disclosed that he couldn’t really work with the theatre folk once the enigmatic figure of Duro Ladipo went the way of the elderly. Ladipo, all splendour and grace, appears as the king in Ija Ominira. Perhaps accidentally, the camera’s long shot evinces a certain pathos in the manner he and his retinue arrive on the scene where the rebel-leader, played by Afolayan, successfully defeats the king’s son, played by Adepoju. There is an eight-minute clip of the film on YouTube, which shows Afolayan’s gifts as a composer and singer, and a self-assured actor. His songs played regularly on the radio in the Eighties, accompanied only by the gwoje.

He did not come out well in my interview with Balogun, and although the filmmaker did not say so directly, it was unlikely from the overall picture he painted that the parting was amicable. Whatever the details, Afolayan went on to produce/direct six other films—more prolific than any of his contemporaries similarly making the transition from traveling theatre to film.

He made other kinds of great art. At least four of his children are prominent figures in Nollywood, the most storied being Kunle, director of highly regarded works such as The Figurine, Phone Swap, and The CEO. A sequence in Ija Ominira shows Afolayan playing the gwoje to serenade his fiancée, and with a close look at his mannerisms one sees a demeanour similar to what Kunle Afolayan demonstrates as Arese in Kelani’s Saworoide, his first Nollywood role. The young prince is tipsy from a bit of drinking and he boasts of his pedigree, using gestures his father has perfected but which the son couldn’t have consciously learnt. It’s in the gene. Kunle’s elder brother, the scholar Shina Afolayan, is on the faculty of the philosophy department at the University of Ibadan. His latest book, Auteuring Nollywood (2014), is a collection of essays on The Figurine, his brother’s best-known film. Another sibling, Gabriel, has appeared in many Nollywood films; he is a gifted, versatile actor.

There is something very instructive about this family story for a view of Nigeria as a history in the making. Looking at the country through the prism of a failed-state narrative, one would not see these distinguished individuals emerging from the profession of theatre, the forte of the riffraff, much less the values they create in their society. Like Afolayan, Moshood Abiola (“Professor Peller”) was an entertainer, a professional magician until his death in August 1997. Like Professor Peller, Olatubosun Oladapo is an entertainer, a poet and composer, with many musical albums and poetry volumes to his credit. To a remarkable degree, their offspring—the nightclub owner Shina Peller and the linguist cultural programmer Kola Tubosun—are among the most visionary shapers of Nigerian life today.

Such, however conservative, is the nature of history. Yet reason doesn’t explain everything. Science cannot reliably explain why people dance.

Akin Adesokan teaches in the Department of Comparative Literature, Indiana University, Bloomington, USA.

END

Be the first to comment