Unfortunately, the act of remembrance, in itself, is somehow beyond our choice, because it is not in our gift to remember ourselves. It is rather foisted on or withdrawn from us by others, whether we like it or not. And it seems there are three categories of remembrance the society can bestow on us.

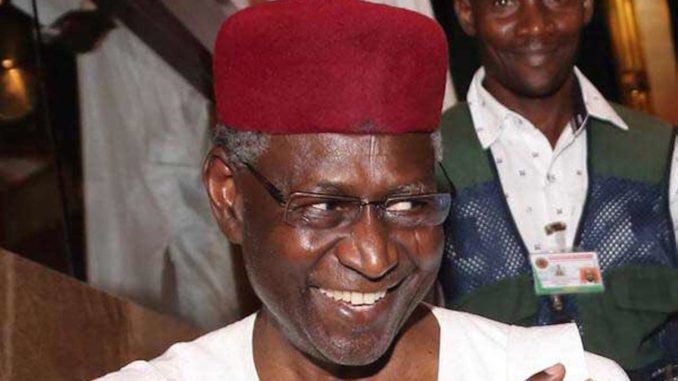

I did not meet Mallam Abba Kyari. I never saw him in person, even from a distance. Destiny did not bring us together in anyway. As such, I cannot claim to know him. Apart from the fact that he was a Nigerian, the other thing we shared in common was the University of Warwick connection, which I only realised from his obituary. While he was at Warwick in the 1970s for his undergraduate studies, I worked as a Research Fellow (2004-2007), and completed my doctorate in political economy and international business within the same time frame, at the same university.

Hence, the much I know of Mallam Abba Kyari is from the seemingly controversial media accounts trailing his death. And from the look of things, he looked like one who was literarily larger than life; to the extent that even in death, he “is” alive and vividly present in society’s consciousness. In a way, one can conclude that he left, but remained with society in other ways.

Following the many comments on him, I wondered how he would be remembered and what he would be known for. He surely held a powerful position, as the chief of staff of the president of Nigeria, at a very interesting time. How he used this position and the other things he did, would be now consigned to history. Moving away from that, I thought that was no longer his question. Instead, it is a question for those he left behind.

In that regard, I wonder what is going on in the minds of those who equally hold powerful positions and are in power today. First and foremost, the politicians come to mind – the senators, the governors, members of House of Representative, local government chairmen, et cetera. Do they think of how they wish to be remembered and what they want to be known for? The same applies to captains of industry, and senior civil servants, knowledge workers, intellectuals, and academics. We shall all die one day. Will history ever be kind to us?

One might quibble and ask: Of what use is it to be remembered? Once one is dead, that’s the end of it, isn’t it? It is for the living to worry about. For such a person, what matters is the here and now. And this consciousness determines how one lives. Short-termism and its satisfaction – no matter how it happens – become the goal. After all, we are all dead in the long run, according to John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), the great British economist.

Unfortunately, the act of remembrance, in itself, is somehow beyond our choice, because it is not in our gift to remember ourselves. It is rather foisted on or withdrawn from us by others, whether we like it or not. And it seems there are three categories of remembrance the society can bestow on us.

…life and living become a journey into nothingness in the Sartrean sense of it. From experience, it seems the majority of people tend to fall into this space of “forgottenness” and permanently remain un-remembered, as nothing. They do not seem to leave any footprints on the sand of history.

The first one, which is rather odd, is collective forgetfulness – i.e. a form of non-remembrance. Literally, one is forgotten. It is a form of existence that passes by unnoticed. One simply appears in and disappears from the world. In that regard, life and living become a journey into nothingness in the Sartrean sense of it. From experience, it seems the majority of people tend to fall into this space of “forgottenness” and permanently remain un-remembered, as nothing. They do not seem to leave any footprints on the sand of history.

The second category is what could be called negative remembrance. People in this category are not forgotten. They continue to live in people’s mind. However, they are remembered mainly for their negative impacts on others. Adolf Hitler, his Nazi, and World War II activities, for instance, will squarely fall into this category. In Nigeria, you may think of some military personnel and presidents, in living memory, who would comfortably fall into this category.

The third category is the space of positive remembrance. People here are remembered for their good deeds and positive impacts on others. As characteristic of negative remembrance, they also continue to live in the mind of society. However, one of the main differences between negative remembrance and positive remembrance is not only their impacts on society, but their reputational disadvantages and advantages to their immediate families and people. Negative remembrance is often a burden on the families of those who are remembered that way. An example is the family of Idi Amin – the former Ugandan dictator – based on the accounts of his family members (e.g. wives and children).

In contrast, positive reputation can be an intergenerational capital and asset. As it is said by some people, “a good name is always better than wealth”. Someone like Samuel Mbakwe – former governor of Imo State – epitomises this saying for Imo people. Despite dying in penury and his shortcomings, he is, to a large extent, still recognised as the best governor of Imo State, so far. His generations are likely to continue to benefit from this reputational asset. Amongst the Yoruba people, Awolowo, seems to enjoy this positive reputation, as well. The name comes across as an excellent brand in Nigerian politics, and the benefits seem contemporaneously glaring.

Abba Kyari ran his race. Unfortunately, he cannot proactively change how history would remember or forget him, no matter what people say or write about him.

Although the act of remembrance may appear beyond our choice, in some ways, it is not completely beyond us, especially if we recognise it and can influence things while we are still alive. Some people have done so. You can think of some brutal business leaders in history, who did their best to turn around their reputation. A classical case here is Andrew Carnegie – the iron and steel merchant who made a fortune in the wake of industrialisation and rail infrastructure in the United States. He was allegedly a brutal entrepreneur who ruthlessly hounded his competitors to remain a monopoly – a venture that made him very wealthy. But before his death, he invested a lot in philanthropy – especially in education (schools and libraries) – as he did not have lengthy formal education himself. Today, Andrew Carnegie’s birthplace in Dunfermline, Scotland, is a museum and a tourist attraction!

Another business mogul and inventor who was able to change his lot was Alfred Nobel. He laundered his image through the creation of the Nobel Prize, which has become a global treasure and measure of excellence. According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, a probable reason for the creation of Nobel Prize was a bizarre incident in 1888: “That year Alfred’s brother Ludvig had died while staying in Cannes, France. The French newspapers reported Ludvig’s death but confused him with Alfred, and one paper sported the headline “Le marchand de la mort est mort” (“The merchant of death is dead.”) Perhaps Alfred Nobel established the prizes to avoid precisely the sort of posthumous reputation suggested by this premature obituary.” So, it is possible to change how one would want to be remembered.

The telling aspect of Alfred Nobel’s story was his concern for a posthumous reputation. The key question then is how we want to be remembered or forgotten. We have the chance now to write our obituaries. We should not allow the opportunity to waste. Life is not just about the here and now. The millions we steal from the national coffers – perhaps to safeguard the future of our generations unborn – can lead to a negative remembrance, which in turn will be a curse rather than blessing to the unborn generations we want to save. Instead, we should use that same zeal to contribute to nation building and leave a positive legacy in history.

Abba Kyari ran his race. Unfortunately, he cannot proactively change how history would remember or forget him, no matter what people say or write about him. May his soul rest in peace!

Kenneth Amaeshi is a public philosopher and professor of business and sustainable development at the University of Edinburgh. He tweets @kenamaeshi

END

Be the first to comment