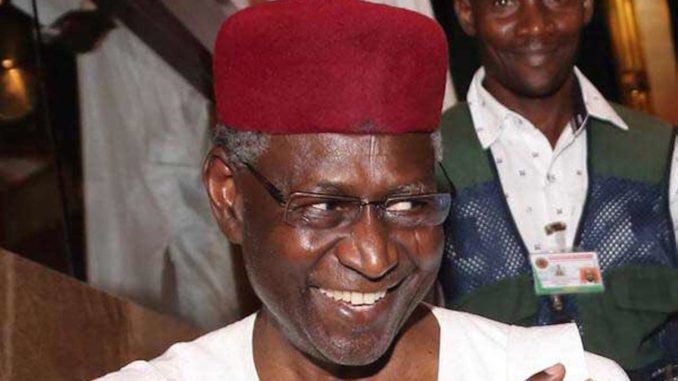

Just a few days ago, Nigerians woke up to the news of its high-profile death so far. Abba Kyari was the chief of staff to President Muhammadu Buhari. And when the Nigerian state came alive to the encroaching pandemic that was already ravaging the rest of the world, Kyari was one of those to be infected in the line of duties. He was in Germany and the UK on official national assignments for the President. And when he returned, he tested positive to the coronavirus. As was to be expected, there was palpable fear about his condition. He was 68 years old and had some existing medical conditions. These facts already cut his chances of surviving the infection by more than half. He eventually lost the fight to the COVID-19 after close to a month of existential struggle. But what really made Kyari’s death a national issue is the existing power dynamics and institutional framework of power that Kyari was a significant part of before he died. He was a chief of staff like no other.

The office of the chief of staff, in especially any presidential system of government, is one that has become a firm fixture of administrative governance. As the designation suggests, the chief of staff is saddled with the managerial and administrative functions of facilitating the running of the presidency in ways that will free up the mind and focus of the president for efficient governance. But the chief of staff is also tasked in an advisory role that demands that he or she provide policy and political advice that will constantly have the interest of the president at its core, while helping the president to negotiate the tough political terrains both within the presidency and outside it with the other arms of government as well as other political actors.

What does that description make of the CoS? How, for instance, does the office differ from that of the executive assistant or the chief operating officer in typical MBA, or if you will, a public administration teaching class? This is a difficult question to ask because it attempts the impossible. The CoS is a catch-all office that stands in between the traditional executive assistant and the COO. It operates in the grey space that include all the regular functions of the two other offices, and many more they do not cover at all.

The CoS is conceived as a strategic partner to the president. Once we understand this analysis, we can begin to come to terms with the status of Abba Kyari and the power dynamics that outline his role as the powerful CoS to President Buhari. Abba Kyari became the CoS in 2015 when Buhari won the election and became the president. And he was reappointed when Buhari won reelection. This fact is a significant one that speaks a lot to how we can get a grasp of Kyari’s status side by side his principal. The office was significantly presaged when Nigeria adopted presidentialism which became entrenched in the 1979 Constitution. The United States therefore became the natural benchmarking guide for how the office of the president operates.

Since 1999 when the office of the CoS emerged and became really functional, four other CoS preceded Kyari, but none was as prominent and as astute as him. In terms of his qualification for the office, no one can impugn Kyari’s credentials. With a degree in sociology and law, and several policy and management posts since 1988 to 1995, as well as economic and banking experience, there is no one else who could have brought to that office a better qualification that Kyari did not possess. Yet, the office of the CoS is not all just about the credentials and qualifications. It is about power and the nature of the Nigerian presidency. The CoS in Nigeria is tied, bolt and all, to the enormous power that the president himself wields. And so, either by default or by commission or omission, the CoS can fill in for enormous presidential powers. In the first instance, the choice of Abba Kyari as the CoS follows the known Buhari style of leadership that seeks out competent and loyal deputies to facilitate the complex business of governance, either governmental or public.

We are all familiar with the famous Buhari-Idiagbon collaboration during the first incarnation of Buhari as head of state. And when he became the executive chairman of the Petroleum Trust Fund (PTF), he brought the same strategy to bear on the running of that task force. But then Abba Kyari was nothing like Idiagbon or all the other CoS that came before him. When Obasanjo created that office in 1999, he meant it to run as an unassuming office with someone in charge who would take administrative charge of his schedules and ensure the efficient running of the office. But then, being so close to the president and holding the managerial responsibilities for coordinating his other principal staff, as well as having the ears of the president on significant policy matters, the CoS must eventually reflect the immense power that the president himself wields. There is nowhere this fact is put in proper proportion than in the United Kingdom where Dominic Cummings is serving as the CoS to Boris Johnson.

In an earlier essay, I attempted to highlight the significant ideological role that Cummings played in the Brexit saga, and how he almost singlehandedly managed the victory that brought Johnson to power. And Cummings was not just a “career psychopath,” as David Cameron characterized him. On the contrary, he was an intellectual and a strategist who has a vision of what the Johnson government ought to be. That is how powerful a CoS can be. And that is how powerful Abba Kyari was. Except that he was powerful in a different sort of way. In Nigeria, we are not talking of a firmly established dynamics of institutional functionality that inserts the prime minister into a complex but ordered relationships with other locus of power. In the context of the United Kingdom and the United States, for example, the president and the prime minister cannot give in to their whims on governmental matters.

There are firm checks and balances. In Nigeria, the Buhari administration practically handed over the presidency to the CoS, and within a context that lacks any crisscrossing institutional checks. This simply means anyone with political power can do whatever he or she likes. Abba Kyari rode on the series of gaps in the presidency to insinuate himself in the power politics that played on his filial relationship with the president. When Buhari, in 2019, mentioned that all requests for meetings should be passed through Kyari, it was at that moment no longer an administrative gatekeeping strategy. The wife of the president had herself already alleged the enormous power wielded by the CoS. There were, for instances, several appointments that were just constitutionally wrong because the CoS is not empowered to make them.

Now, Abba Kyari is dead. And all the outpouring of emotion by friends and families is, I think, a little too late for two reasons. First, none of them so far, including those who have vilified him, has establish a beyond-reasonable-doubt proof as to how Kyari has misused his immense power. It is not sufficient to throw around the MTN bribe issue or to allude to Kyari’s “self-appointment” to the board of NNPC, for instance, as if they are self-evident facts of abuse.

It is also not sufficient to project what Kyari told friends in private conversations as “proof” of his saintliness. Friends must know that power corrupt, and absolute power transforms absolutely. But the second issue is more fundamental: no one could doubt that Abba Kyari was more than a mere CoS gate keeping Buhari’s office. The idea of a “surrogate presidency” has been afloat since Kyari came into the prominent limelight, and that term best convey the dangerous tangent that the office of the CoS has moved since Kyari assumed its mantle.

In the first place, the idea of a surrogate presidency totally violates the tenets of democratic governance, and of the presidential system of government. Even within the ambit of the presidential system that Nigeria adopted, no CoS must be so powerful as to displace the elected representative of the citizens’ democratic will. This amounts simply to a betrayal of the trust invested in the president by the people to implement policies that would impact positively on the lives of the people. No time is this more fundamental than the period of the COVID-19 pandemic when decisive governmental action is needed. In the second place, the idea of the surrogate presidency is deeply mired in the dirtiness of realpolitik—the complicated dynamics of maintaining power—that sucks life out of any attempt at efficiently and effectively deploying governance towards the well-being of Nigerians.

The death of Abba Kyari is a painful one (to the extent that all deaths at this time are painful), especially for the president, and for family and friends. But it is a cogent one that Nigeria needs to take serious as an indicator of one of the fundamental things that is amiss in a presidency that has been anything but efficiently functional. And there is no other time to commence such a reflection on the repurposing of the office of the CoS and of the presidency itself as a whole than now when Nigeria stands at the heart of a continental pandemic outburst that bodes no state and its people any good. The process for appointing another CoS must have commenced. And it will be pure insensitivity if politics takes the first place in the considerations for appointing someone who has the capacity to push the president into an efficient performance of his office.

Prof. Olaopa Permanent Secretary, State House, Abuja (rtd.)& Professor of Public Administration, wrote from Ibadan.

END

Be the first to comment