No country is fully equipped to deal with the next global pandemic, a major report has claimed.

Scientists say an outbreak of a flu-like illness could sweep across the planet in 36 hours and kill tens of millions due to our constantly-travelling population.

But a review of health care systems already in place across the world found just 13 countries had the resources to put up a fight against an ‘inevitable’ pandemic.

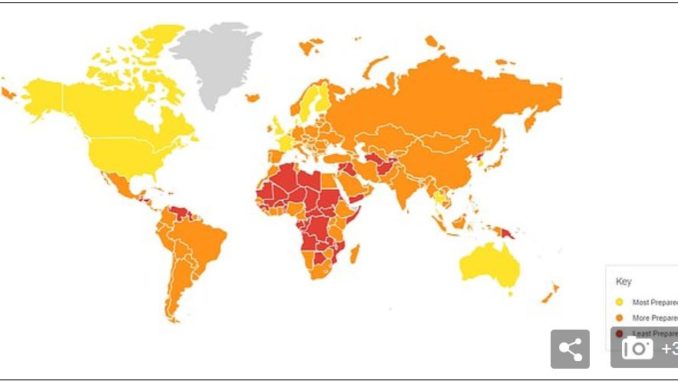

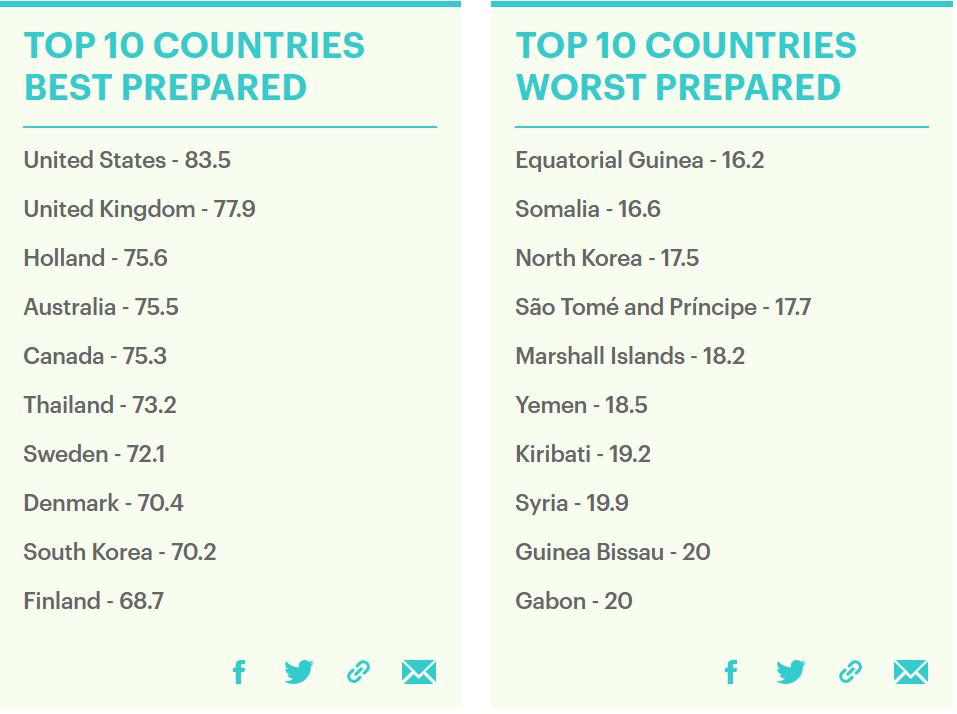

Among the countries ranked in the top tier were Britain, the US, Australia, Canada, France and Holland.

But given how fast the outbreak is likely to spread, experts warn even these nations may struggle to curb the disease.

Most of the EU 28, including Spain, Germany, Italy, Austria and Norway, were considered ‘more prepared’, a tier below Britain and the US.

Whereas the majority of Africa was deemed the ‘least prepared’ of all the countries due to poor immunisation .

The sobering report, known as the Global Health Security (GHS) index, was drawn-up by scientists at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, and the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI).

In their recommendations, the team said governments must ringfence money for putting preparations in place and do routine simulation exercises.

They also called for more private investment into countries’ pandemic preparations and said the UN must do more to co-ordinate responses across international borders.

The scientists assessed how countries around the world would deal with an inevitable pandemic, by looking at a range of factors.

Income, border security, health care systems, as well as political, socioeconomic and environmental risk factors that can limit response, were all considered.

The average overall index score was just over 40 out of a possible 100. Scientists say this points ‘to substantial weaknesses in preparedness’.

But they found that even among the 60 high-income countries assessed, the average score was barely over 50.

Writing in their report, the scientists said: ‘The Index, which serves as a barometer for global preparedness, is based on a central tenet: a threat anywhere is a threat everywhere.

‘Deadly infectious diseases can travel quickly; increased global mobility through air travel means that a disease outbreak in one country can spread across the world in a matter of hours.’

The report comes a month after a group headed by a former World Health Organisation (WHO) chief issued a stark warning that Disease X was on the horizon.

The report, named A World At Risk, said current efforts to prepare for outbreaks in the wake of crises such as Ebola are ‘grossly insufficient’.

It was headed by Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland, the former Norwegian prime minister and director-general of the WHO,

He said in the report: ‘The threat of a pandemic spreading around the globe is a real one.

‘A quick-moving pathogen has the potential to kill tens of millions of people, disrupt economies and destabilise national security.’

He claimed that previous recommendations about the threat of a global pandemic have been largely ignored by world leaders.

The team drew up a map of the world with a list of possible infections which could trigger the hypothetical outbreak.

These were split into ‘newly emerging’ and ‘re-emerging/resurging’. Among the former were the Ebola, Zika and Nipah viruses, and five types of flu.

And the latter included West Nile virus, antibiotic resistance, measles, acute flaccid myelitis, Yellow fever, Dengue, plague and human monkeypox.

The report referenced the damage done by the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic and said modern advances in international travel would help the disease spread faster.

A century ago the Spanish flu pandemic infected a third of the world’s population and killed 50million people.

But more recently an Ebola epidemic in West Africa claimed the lives of more than 11,000 people.

Another outbreak of the deadly virus has killed 2,100 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the fatalities are rising.

Leo Abruzzese, senior global advisor at The Economist Intelligence Unit, who helped compile the report, said the report helped to identify important gaps in global preparedness.

‘Without a way of identifying gaps in the system, we’re much more vulnerable than we need to be,’ he said.

‘The index is specific enough to provide a roadmap for how countries can respond, and gives donors and funders a tool for directing their resources.’

END

Be the first to comment