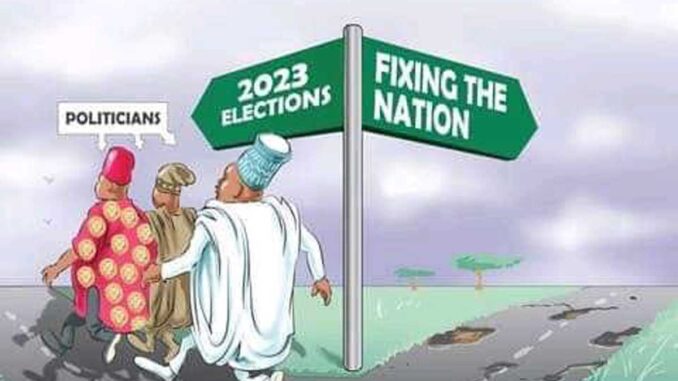

The significant year 2023 is still some eight months away, but the Nigerian political space is already feeling the weight and heat of electoral matters, especially with several candidates—presidential and gubernatorial—already signaling their intentions to contest. As at the writing of this piece, 18 candidates from the All Progressives Congress (APC) and the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) have already signaled their intention to contest the position presently occupied by President Muhammadu Buhari.

This number of candidates, and as many that would be joining the list, only signals how critical the year 2023 has become in Nigeria’s political calculation. And this is because the last eight years of President Muhammadu Buhari’s (PMB) administration has been a very rough ride and confounding, especially in security and governance terms.

Given current reality with critical development indices, the crisis of the Nigerian state and the future of the Nigerian project of national integration have become somewhat more complex in measures that will be more demanding for future leadership. Under the onslaught of the Boko Haram insurgents and the banditry associated with the Fulani herdsmen, the security problem has become increasingly worse, with kidnapping, banditry and criminality becoming rampant across the country.

The security predicament is further compounded by governance matters—from poverty to unemployment to industrial unrest and galloping inflation. Fortunately, or unfortunately, those who want Buhari’s seat will also soon begin to campaign on the capacity to restitute the policy deficits of the current administration around security and governance. And Nigerians would be expected to make a tough choice at the polls, come 2023.

For me, the most critical absence in the gathering political storm for 2023 is the lack of any ideological frames around which to hang the tussles and electoral campaigns of the parties that are emerging and fielding candidates at both the presidential and gubernatorial levels. In other words, the two political parties—APC and PDP—both are distinguished by their conspicuous lack of ideological base around which significant issues, from security and the economy to public service reform and unemployment, can be distinctly articulated as campaign manifestoes.

As part of her political development after independence, Nigeria adopted presidentialism from the political experience of the United States. The concept of presidentialism in the U.S. gave birth to two ideologically rooted parties, the Republican and Democratic parties. Every significant issue in the American political space—from same sex marriage to racism—are determined on the spectrum of liberalism and conservatism around which the two parties revolve. And this is the backbone that speaks to the political dynamics that uphold good governance.

Good or bad governance is determined by the kind of politics that the political class play with the lives of their citizens. The objective of all political parties everywhere in the world is to contest for power as a means to an end, which is the determination of the trajectory of development that the ideology the party holds, will take the country. An ideology therefore becomes a vision of politics attached to development. Thus, for instance, while Republicans prefer the free-market approach to healthcare that prevents the government from intervening in healthcare provision, the Democrats queue behind the universal health coverage and single-payer system. Thus, when ideological political parties gain control of political power, there is already a blueprint of policies and actions to be taken on behalf of the citizens. This is what happens in the United States. This is also what happens in Britain, and indeed in Europe. It is a far cry from the clueless politics that goes on in Nigeria where the political class is devoid of ideologies that determine what to do on significant issues.

We can then begin to ask the fundamental question that should circumscribe our thinking about 2023: the relationship between ideological and issue-based politics and good governance; and why the future of Nigeria depends sorely on what ideology we need to run the Nigerian state and make development happen for the citizens. In 2015, PMB rode to power on an integrity brand and an un-interrogated change agenda—the no-nonsense mien of a never smiling president who will discipline the place and restore security of life and property. The closer we move to 2023, the more it is dawning again on us that ethnicity, religion and the power of incumbency remain the critical factors that would determine who becomes the president in 2023. And the laugh seems to be at the expense of me and all those who expect that the Nigerian political climate is ripe for an issue-

based political engagement among the political parties.

This is the lesson I got in a conversation with a gubernatorial candidate in the 2019 election. I was bristling in my analysis of how his adoption of strategic communication could serve as the platform for an ideology-rooted engagement. He laughed at me! His response: people are not concerned with issue-based politics on the campaign field. All that matter is “stomach infrastructure”!

And yet, this was not how the Nigerian state and her politics was envisioned and inaugurated. Nigeria’s nation-building and political development trajectory began most significantly with the best political motif. Pre-independence campaign was energized by ideology-rooted nationalist movements. For instance, the Anglo-Nigerian Defence Pact became the source of a frenzied ideological opposition motivated by pan-Africanism and the non-aligned movement. This was the type of ideological contestations around which the political parties, especially in the First Republic, were known for.

Indeed, the nationalists were confronted with the future prospect of a nation that had just emerged from the womb of colonialism. It is in this context that we can understand the Nigeria-as-mere-geographical-expression thesis of Chief Obafemi Awolowo, and the diarchy ideological recommendation of Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe. No one would forget the political rivalry between the Action Group, Northern People’s Congress and the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroun (as well as the reincarnation of the rivalry between the NPN and the UPN). Or the People’s Redemption Party of Mallam Aminu Kano. Indeed, the Nigerian Political Bureau, set up by the regime of President Ibrahim Badamosi Babangida, had fundamental ideological recommendations that are still relevant for putting Nigeria together on a firm political footing. Nigeria’s return to democratic rule, signaled by the June 12 saga, also signaled the ideological extent that Nigerians could go in tracking political development in Nigeria.

The question now is: where did all this go? Where did we miss it? What has happened to the type of political contestations that enlivened political engagement from the post-independence period all through the First to the Second Republics? This is a fundamental question that becomes all the more insistent against the background bare-faced power grab of the existing political parties without the complement of an ideology that constitute a blueprint for ordering Nigeria’s future. And if the political parties lack a sense of history that it is ideology that shape the political development of a state for good or for ill, how then can they be placed in the seat of power to run the most populous black nation on earth? How can national development and national integration ever happen in Nigeria if ethnic jingoists, religious fundamentalists and greedy politicians are the ones that constitute the choice of who to vote for? Truth be told, neither the APC nor the PDP has the organizing frameworks to dimension the future of the Nigerian state, especially in terms of political education, mass mobilization, interest aggregation and delimiting national discourse about Nigeria’s future. Which is why the tomfoolery of decamping from one side to the other has become such a normal play for politicians.

Come 2023, Nigeria would be committing another eight years of her future to a set of political office holders who have no sense of political history, ideological commitment or a vision of where Nigeria ought to head. The political space will soon be awash with obscene money taken from the common treasury, and deployed to seal the critical voices, especially of the youths that ought to be stringent in asking for vision, and blueprints and ideology. But once money has exchanged hands, the unscrupulous politicians are already given the unbridled license to ransack Nigeria’s treasuries for their personal and selfish ends.

And 2023 to 2026, and perhaps beyond, would have become a wasted effort in consolidating Nigeria’s future. If this scenario is possible, why are we not asking the right questions about 2023? Why are we not already signaling the fundamental significance of ideologically-rooted and issue-based politics as the benchmark around which we can begin to engage with all the political parties already jostling for political power? Why are the individuals more important than the critical questions we ought to be asking?

Olaopa is a retired Federal Permanent Secretary and Professor, National Institute For Policy and Strategic Studies (NIPSS), Kuru, Jos. tolaopa2003@gmail.com

END

Be the first to comment