In kicking out the current national leadership, we may not get the vote right next year (as we obviously failed to do in 2015). But Nigeria deserves a healthier, more knowledgeable, and more inclusive leader if we are really to make a decent fist of governance in our rapidly-changing and technologically-demanding world.

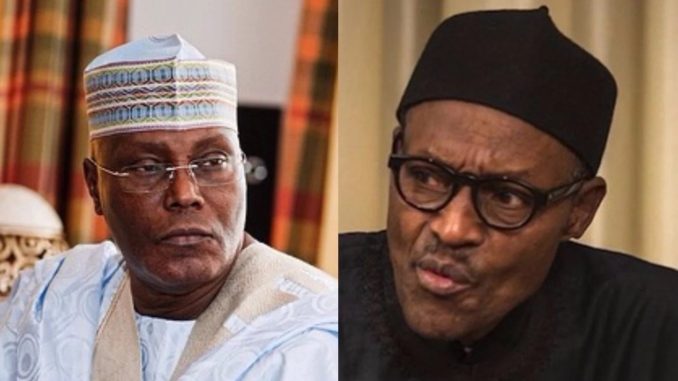

It is hard, in the light of the tumultuous developments in the nation’s political space last week, to continue to pretend to an antiseptic distance from popular concern over the outcome of next year’s general elections. The emergence of Mr. Abubakar Atiku as the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP)’s candidate for president has sharpened these concerns — as has his endorsement for the office by former President Olusegun Obasanjo, and several other éminence grises. Usefully, such is the nature of the incumbent administration’s record in office that it is almost impossible to be neutral in this matter.

About this same period in the last electoral cycle, my biggest worry was that despite his evident lack of suitability for office, a maudlin sentimentality might see Nigerians return Goodluck Jonathan to office. I believed then that that was the worst of the many options before the economy. Arguably, in discussing Nigeria, the one oppressive feeling that is hardest to shake off is this sense of going around in circles. For as with the 2015 elections, when we were willing to wink at the anti-democratic instincts of the All Progressives Congress (ACP)’s presidential candidate, we are again at that point where we may be minded to shrug off alleged flaws in the character of the opposition candidate simply to turf another incompetent serving president out of office.

Yes, President Buhari has not been as competent as he was once advertised. Nor has he proved any better at managing the economy than did Jonathan. Incidentally, this is not about his ill-health. Or his unwillingness to fess up to what ails him. Or the many days he spent out of office as a guest of the U.K.’s National Health Services (NHS). Nor is it about the eternity it took him to set up shop once elected president. Though, the latter phenomenon was indeed most dreadful. He had had two previous failed shots at the presidency, so how could his government turn catatonic when it mattered most that it was addressing the myriad tasks for which it was voted into office? And the Jonathan administration had steered the ship of state as close to the shore as it was possible to without beaching it. Still, it took our reforming president the better part of six months to put his cabinet together. The cabinet turned out to be nondescript in the end.

At that point, many of us were not really bothered. After all, there was that 800-page document put together by the Ahmed Joda-led transition committee. I had no doubt that, implemented properly, we had a roadmap out of the then crisis. Those who would today demonise my opposition to the re-election of Mr. Buhari as president next year, would do well to remind us of what became of that document. That the president did not read it, there is no question.

…nearly four years of the Buhari administration has left the Nigerian state materially unchanged. Promised reforms to the public sector (including early hopes of implementing the Oronsaye report) have been binned. Inflation continues to erode the people’s purchasing power. Even as the ratio of job seekers to new jobs multiplies.

Otherwise, we would not have a situation where his government believes that the solution to the nation’s infrastructure constraint is to throw more government money at the problem. Thus defined, we have spent four years constricting the private sector’s capacity to boost supply. How do I mean? With oil prices far lower at the beginning of the Buhari administration’s tenure, it had to borrow most of the money it needed to drive its infrastructure targets. It began by borrowing from the domestic economy. Driving up rates in the process. Higher rates, in turn, meant that the private sector no longer was able to borrow from the banks. And so, the economy was always bound to contract on the back of the Buhari administration’s cack-handed policies.

It did not matter that oil prices then tanked, taking the economy further into recession. It has mattered instead that the country has borrowed against future earnings up to a point where current earnings clearly are not able to support our debt service needs, while still leaving something for our daily requirements. It is possible to argue that because of the long lag between when infrastructure investment is completed and when they begin to drive productivity improvements, the positive pass through from the huge debt portfolio will take some time to show up in national output numbers.

But that is to suggest that our borrowing thus far has been part of a programme. Since we do not know what became of the transition committee’s report, this line of thought demands that we ask what blueprint the government has been running on. This question is not as academic as it sounds. Next year, domestic output growth will still be as dependent on the global oil market as it was in 1970. In other words, nearly four years of the Buhari administration has left the Nigerian state materially unchanged. Promised reforms to the public sector (including early hopes of implementing the Oronsaye report) have been binned. Inflation continues to erode the people’s purchasing power. Even as the ratio of job seekers to new jobs multiplies.

Some have argued that Mr. Buhari’s mandate was not to resuscitate the economy. Instead it was to do battle against corruption… It was that at no point in the playing out of the respective dramas did he provide insight into his thinking on the matter, nor the kind of leadership that assured the country that it was no longer business as usual.

Confronted by these numbers, boosters of the Buhari administration are wont to bandy facts that prove that the last PDP administration was no better. So much for moral equivalence, and the many fallacies that support it! For if we turfed the Jonathan government out on the strength of that record, it behoves us to visit similar action on the incumbent president. Two other fiascos do not reassure. “Nigeria Air” was a national embarrassment that questioned the national capacity for planning ― if not our general aversion to ethical behaviour. And then there was the controversy in 2015, when most commentators were sure that the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) was in breach of its own statutes, having lent to the federal government more money that year than 5 per cent of the prior year’s revenue. There are cads who now claim that the CBN’s failure to publish its annual report and accounts for that year owe to its reluctance to document a fraud.

Some have argued that Mr. Buhari’s mandate was not to resuscitate the economy. Instead it was to do battle against corruption. But then there was Babachir David Lawal (and his lawn mowing skills) and Kemi Adeosun (and her certificate scandal). It was not so much that these happened under our incorruptible leader’s watch. It was that at no point in the playing out of the respective dramas did he provide insight into his thinking on the matter, nor the kind of leadership that assured the country that it was no longer business as usual.

For these reasons and a lot more, I will not be voting for Mr. Muhammed Buhari next year. In kicking out the current national leadership, we may not get the vote right next year (as we obviously failed to do in 2015). But Nigeria deserves a healthier, more knowledgeable, and more inclusive leader if we are really to make a decent fist of governance in our rapidly-changing and technologically-demanding world.

Uddin Ifeanyi, journalist manqué and retired civil servant, can be reached @IfeanyiUddin.

END

Be the first to comment