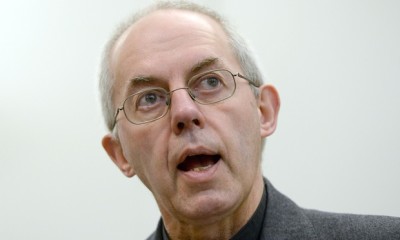

Justin Welby’s vision for communion is solution to seemingly irreconcilable differences between churches

Justin Welby’s vision for communion is solution to seemingly irreconcilable differences between churches

Justin Welby, the archbishop of Canterbury, is set to propose a radical new vision for the Anglican communion of international churches. But what is it? And what could the implications be for the church’s powers here and abroad?

What is the Anglican communion?

The Anglican communion is an association of independent Anglican churches from 38 provinces. With 80 million members, it is the third largest Christian body in the world, after the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches.

Each of the 38 provinces has a chief bishop or archbishop, known as a primate. Confusingly, the provinces can be individual countries – such as Brazil, Bangladesh, Scotland or Wales – or a group of countries. For example, the Church of the Province of Central Africa encompasses Botswana, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Or a country can have more than one province. India has two: the Church of North India and the Church of South India.

These churches are all Anglican, but they are culturally extremely different, leading to bitter disputes between some of the more conservative and liberal members.

The archbishop of Canterbury is the head of the Anglican communion by precedent, but his role is that of primus inter pares (first among equals), and he has no direct authority to tell the different churches what to do.

All the Anglican bishops from around the world usually meet every 10 years in Canterbury at a Lambeth conference, though that has been indefinitely suspended by Welby.

What does Welby want to change?

The Anglican communion is bitterly divided, particularly over issues of sexuality and women, and Welby is set to propose that it is no longer effective, and has not been so for 20-odd years.

He has summoned all of the 38 primates to a meeting in Canterbury next January to propose that the communion be reorganised as a group of churches that are all linked to Canterbury, but no longer necessarily to each other.

Welby’s predecessors, Rowan Williams and George Carey, worked hard to use the Anglican communion to facilitate liberal and conservative church movements working together, but on issues of sexuality in particular there has been little common ground to work with.

A Lambeth Palace source described the change to the Guardian as not like a divorce but “more like sleeping in separate bedrooms”.

What’s been the issue?

There is deep ideological difference between churches in the Anglican communion. In North America, liberal churches that come under the Anglican banner are able to recognise same-sex marriages, while in African countries such as Kenya, Uganda and Nigeria, church leaders press for the criminalisation of all homosexual activity.

The change is tantamount to an admission that the Anglican communion is too worn a thread to hold some churches together when their feuds are so great.

At the last Lambeth conference, in 2008, more than 250 bishops out of 800 stayed away in protest at the liberal sympathies of the then archbishop, Rowan Williams.

Welby has indefinitely postponed the next conference, which would have taken place in 2018.

What will happen now?

The Church of England will remain linked to all of the provinces in the Anglican communion, but they will not have formal ties to each other. All churches will still be able to call themselves Anglican.

Welby will hope that relationships and cooperation between national churches will continue on issues less toxic but still of vital importance, such as climate change and the persecution of Christians by extremists in the Middle East, Africa and south-east Asia.

If everything goes to plan, Welby hopes to hold a meeting of those bishops from Anglican churches that remain committed to working together in 2020.

What could go wrong?

The African churches, known as Gafcon, many of whom have made no secret of their distaste for the more liberal concessions by the English church in recent years, may decide to withdraw from any link to Canterbury.

That would not in itself be too disastrous, apart from the fact that Welby has prided himself on his ability to work effectively with conservative churches in Africa since his time before becoming a bishop working on missions of reconciliation in countries such as Nigeria.

More damaging would be if Gafcon convinced swaths of evangelical churches in England to withdraw from any affiliation to the Church of England. Some have already left.

In the US, where relations have been deteriorating since the mid-90s, Anglican churches from Nigeria, Rwanda and Kenya have set up their own congregations.

Welby may also have offended the liberal American Anglican church body by inviting a breakaway conservative US church, the Anglican Church in North America (Acna), which is not officially part of the Anglican communion. Acna was formed following a rift in 2003 when the original US Anglican body decided to ordain Gene Robinson, an openly gay bishop.

END

Be the first to comment