Professor Toyin Falola stands at the core of…efforts to rethink and restructure the way we think about the humanities, the development initiatives and higher education in Nigeria. And these alone recommend his unique scholarship and intellectual contributions for critical commendation…

My celebratory critique of those I have been calling intellectual heroes and heroines has the objective of not just achieving some sort of breakdown of Nigeria’s intellectual history. More importantly, it is meant to outline, in a critical manner, the contributions of these figures to the rethinking and the reinvention of Nigeria’s historicity and national trajectory as a postcolonial development space. From Billy Dudley to Eni Njoku, from Bolanle Awe to Wole Soyinka, and from Claude Ake to Gambo Sawaba, from Bala Usman to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, I have outlined the crucial performances and contributions of educationists, scholars, teachers, activists, jurists and lawyers, historians and medical practitioners, civil servants and clergy, philosophers and politicians to the Nigerian project. Each of these intellectuals and public figures has some peculiar complexity attached to the narrative of his or her life. For instance, narrating the contributions of Funmilayo Ransom-Kuti is far different from the achievements of Ojetunji Aboyade or Ken Saro-Wiwa. And I have approached each hero and heroine with some form of trepidation that bothers on the anxiety of adequately capturing that which is best and proper in the lives and achievements of these significant citizens, without seeming to fawn.

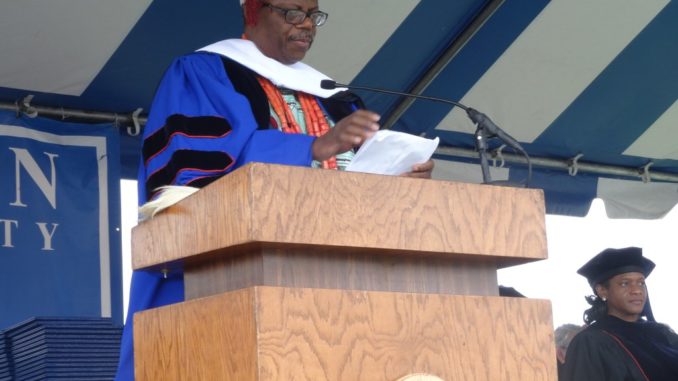

However, the moment it occurs to me to do a piece on Professor Toyin Falola, the Jacob and Frances Sanger Mossiker chair in the Humanities at the University of Texas at Austin, United States of America, it dawned on me that I have finally met an intellectual complexity itself. How do you capture Falola’s being, life and achievement? How do you narrate the history of a historian who has achieved a global presence that is essentially historic? How do you fit into a short piece a flourishing life that is already well lived? Toyin Falola has already done for the discipline of African history and the field of African Studies, what W. E. B. du Bois did for Negro studies, and Cheikh Anta Diop did for pan-Africanism. I came to him with the same kind of awe that attends my consideration of the scholarly activism of Kenneth Dike, the trailblazing achievements of Claude Ake, the combative intellectual advocacy of Ali Mazrui, and many more.

Professor Toyin Omoyeni Falola represents all that is the best in Africa’s global intellectual presence. This is a critical point for me because the idea of the diaspora is a complexity that has swallowed many of Africa’s best and brightest. Several reasons led to the loss of Nigeria’s intellectuals to the growing Nigerian diaspora. But a dominant theme in Nigeria’s intellectual circle has been that of despair at the increasing disconnect between those outside the Nigerian state and those within it. This chasm between those within and those without leaves a void in the national development project. It is within this chasm that I want to situate Toyin Falola’s relentless intellectual effort on behalf of Africa and Nigeria. Fortunately for us all, the diaspora has not swallowed this intellectual giant who looms very large at home and abroad and across the globe. He is as much visible at home here in Nigeria as he is in Europe, the Caribbean and everywhere else, flying Africa’s intellectual and cultural flag.

At a time when the Nigerian state is still struggling with the significance of history as a discipline, and more significantly at a time when the historical trajectory of Nigeria is hitting several critical bumps arising from the calling into question of her status as a legitimate nation, Falola’s intellectual dedication to the discipline of history provides a refreshing reassurance that Nigeria is making a huge mistake by being ambivalent about her own historical dynamics and complexities. The Nigerian state exists as if it is afraid of her historical trajectory. Abolishing history is one national policy, alongside many others, that reveals certain developmental blindness in the Nigerian governance framework. The angst about keeping Nigeria united has created an intolerant national atmosphere that, paradoxically, is tearing Nigeria apart.

…Falola is confronted with the herculean challenge of not only traversing the complexities of the humanities themselves—philosophy, history, literary criticism, religious studies, music, etc.—but he is also tasked with the responsibility of defending the humanities and outlining their relevance to Africa’s reinvention and development future. And he comes to these tasks with vigour and relentless enthusiasm.

However, when Falola intervenes in this conundrum, he does so from a larger intellectual perspective that drags history into the complex global template of the African humanities, and their historical mandate in Africa and Nigeria. The humanities everywhere is under a global intellectual siege. The African humanities are in even worse dire strait not unconnected with the severe underdevelopment of the continent. The critical issue is that in the urgent bid to transit from postcolonial underdevelopment to achieving a development profile that compels global recognition, there is a crucial need to rethink the relevance of higher education and the universities to that urgent objective. Most African states fail, subsequently, to see where the humanities fit into the larger picture. This explains why a country like Nigeria will consider the unthinkable educational policy of abolishing history in secondary school as a discipline whose development credential is in doubt. With an endowed chair in the humanities, Professor Toyin Falola is confronted with the herculean challenge of not only traversing the complexities of the humanities themselves—philosophy, history, literary criticism, religious studies, music, etc.—but he is also tasked with the responsibility of defending the humanities and outlining their relevance to Africa’s reinvention and development future. And he comes to these tasks with vigour and relentless enthusiasm. In The Humanities in Africa, Falola presents a complex trajectory of arguments and contestations that reaches across several frameworks and trajectories, from the global to the national to the localities of the humanities themselves. He juxtaposes the humanities in between the global emergence of a capitalist economy and the urgency of local imperatives.

Falola – Humanities in Africa

When parents react negatively to their children taking any course in the humanities, say history, it is because they have constructed a framework of future prospect that has been shaped by global capitalism and the economy of success. The issue, therefore, is that of how History, Philosophy, English, Linguistics or Music can serve as a significant platform upon which a future investment portfolio can be built that will, for instance, enable children to take care of not only themselves but also their parents who are presently labouring to send them to universities and other tertiary institutions. How do the humanities react to these legitimate expectations? How should the humanities react to Africa’s legitimate concerns about her own development trajectory? These are critical questions that have become all the more urgent within the context of two looming developments. The first is the arrival of the global information and knowledge society that demands more in terms of the application of knowledge to national advancement. The knowledge society is essentially an emergent global society that demands the deployment of relevant knowledge. And what constitutes “relevant knowledge” is globally constructed by capitalism.

The second global challenge to the humanities derives from the arrival of the STEM disciplines. This development is a significant consequence of the capitalist construction of relevant knowledge. STEM—science, technology, engineering and mathematics—constitute a significant revolution in curricular reorientation that pushes higher education into the context of global and national development discourse. STEM effectively consolidates the downward spiral of the humanities into looming oblivion. STEM does not need to be defended because it provides an obvious and immediate template of developmental curriculum that speaks to Africa and her postcolonial development predicaments. With the new stipulations contained in the STEM pedagogy, African states can then begin to consolidate their initial belief in the sciences as the engine room for national development. One only needs to scrutinise, for example, Nigeria’s National Policy on Education (NPE) to tease out an educational policy that is founded on the need to develop an educational system and paradigms that will service Nigeria’s development objectives through the constant and efficient production of skilled and “functional” graduates. These graduates are then expected to form the solid foundation of a human capital dynamic that the Nigerian state can deploy effectively to her national development imperatives.

Professor Falola’s construction of the relevance of African humanities is an extremely nuanced one that dispenses with several orthodox assumptions and stale arguments. One of the most significant is the understanding of the relationship between the humanities and STEM as one of antagonism.

Unfortunately, Nigeria’s higher education is still disconnected from her development objectives despite the vast army of graduates that enter the job market yearly. On the one hand, there is already a perception of a differential disconnection between the humanities and the sciences in jumpstarting development that fractures the capabilities of what ought to be the collective and concerted effort of tertiary education in Nigeria. Everyone wants to attend the universities. The polytechnics and the colleges of education get left out of the development equation. On the other hand, those who attend not only the universities but other institutions, graduate with a firm belief in white collar jobs. And since these jobs are not readily available, youth unemployment effectively undercuts the relevance that higher education ought to contribute to national development. Thus, even if STEM gets entrenched into the Nigerian educational system as the curricular and pedagogical template of choice, it still would not translate into an instant development game changer. So many things are already wrong.

Professor Falola’s construction of the relevance of African humanities is an extremely nuanced one that dispenses with several orthodox assumptions and stale arguments. One of the most significant is the understanding of the relationship between the humanities and STEM as one of antagonism. For him, when the scholars of the humanities defend their disciplines, they often do so against the background of the essential differences between the humanities and the sciences. Therefore, within this logic of exclusion, the humanities’ relevance must be drummed into the ears of everyone, and especially of the Nigerian government. It therefore becomes the norm that the relevance of humanities to development must always be constructed against the relevance of the science and of STEM. But this assumption of exclusion and antagonism is a deeply faulty one that could only do more harm to our perception of the relationship between higher education and national development. This is because the logic of opposition between the sciences and the humanities occludes the fact of what Falola calls intersectionalities. To create the linkages between STEM and the humanities, we first need to underscore the weaknesses of the two. On the one hand, STEM education has failed to deliver the promised development it promises. On the other hand, the humanities have also failed to underscore their own relevance to the development imperative. But integrating the one into the other poses more possibilities for arresting Nigeria’s, and Africa’s, development impasse. However, intersectionality requires more than the entrenched insularities have been built into our curriculum. It demands a creative curricular and pedagogic creativity that lead, in the final analysis, to a robust human capital that will understand the demands of the time and the variables that can launch Nigeria’s development initiative.

Professor Toyin Falola stands at the core of these efforts to rethink and restructure the way we think about the humanities, the development initiatives and higher education in Nigeria. And these alone recommend his unique scholarship and intellectual contributions for critical commendation as the endeavours of an intellectual whose reflections challenge the way we think about Nigeria and Nigeria’s being in the world.

Tunji Olaopa is executive vice-chairman, Ibadan School of Government and Public Policy (ISGPP); Email: tolaopa2003@gmail.com, tolaopa@isgpp.com.ng

END

Be the first to comment