Fidel Castro’s death came more than a decade after the Cuban revolutionary and authoritarian first handed power to his brother Raul during a severe illness. Castro resigned permanently in 2008, prompting then-President George W. Bush to declare his hope for a democratic transition and vowing that “The United States will help the people of Cuba realize the blessings of liberty.”

Cubans have not yet realized them. Raul Castro began to open Cuba’s economy, and accelerated that opening through a rapprochement with the United States beginning in 2014, which later saw President Barack Obama nominate an ambassador to the island for the first time since the Eisenhower administration and significantly loosen America’s five-decade trade embargo. But Cubans still could not choose their leaders; as Human Rights Watch noted: “Many of the abusive tactics developed during [Fidel’s] time in power—including surveillance, beatings, arbitrary detention, and public acts of repudiation—are still used by the Cuban government.” While Obama offered a measured statement on Fidel’s death, declaring that history would judge his legacy, Cuban American members of Congress were blistering. “A tyrant is dead,” remarked Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, a Florida Republican representative. “Castro’s successors cannot hide and must not be allowed to hide beneath cosmetic changes that will only lengthen the malaise of the Cuban nation.” The Cuban blogger Yoani Sanchez declared on Twitter that Castro’s legacy was “a country in ruins, a nation where young people do not want to live.”

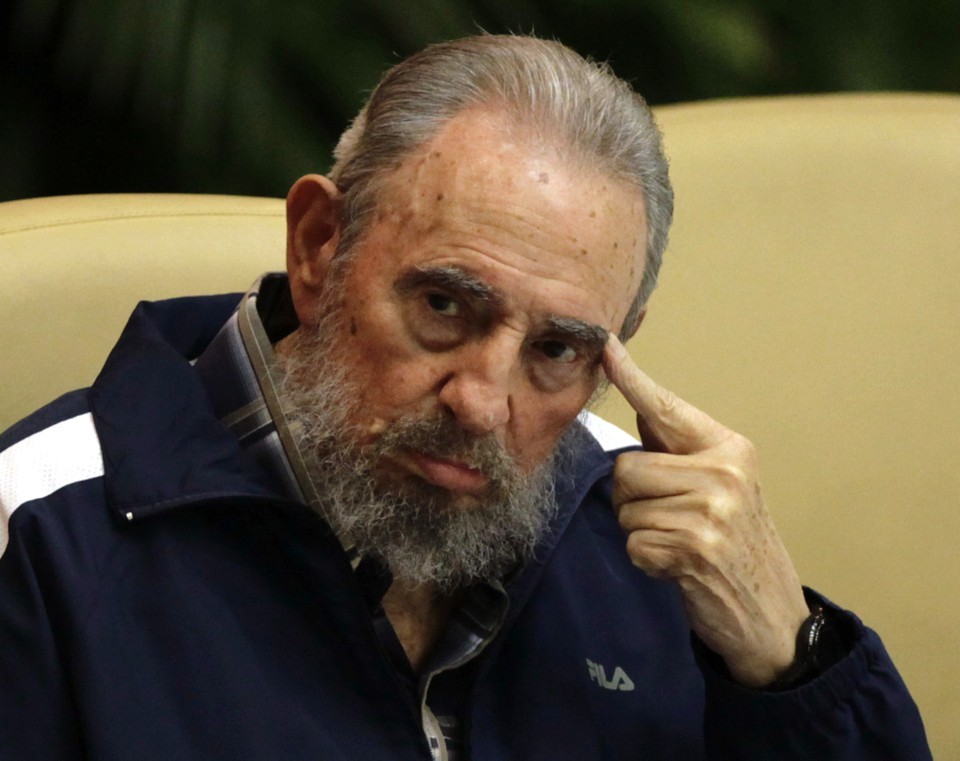

The morning following the announcement of Castro’s death, I spoke with Peter Kornbluh, the co-author of the recent book Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana, which chronicles the countries’ history of discord and long path to normalized relations. Kornbluh is one of the leading historians of U.S.-Cuban relations and had spoken to Castro several times; he describes himself as a lifelong advocate of normalized relations, out of the belief that the decades of hostility that only recently began to thaw served neither the United States nor the Cubans still waiting for the blessings of liberty. (As Jeffrey Goldberg notes, Fidel himself “reveled in his half-century confrontation with America, and, he knew, I believed, that it would be more difficult for Cuba to resist battalions of Yankee capitalist hoteliers and an invasion fleet of Fort Lauderdale-based cruise ships than it was to defeat the hapless landing party at the Bay of Pigs.”) What follows is a transcript of our conversation, condensed and edited for clarity.

Kathy Gilsinan: As a very basic question to start, how in your assessment did Fidel manage to hang on for so long?

Peter Kornbluh: Fidel Castro was one of the world’s longest-serving leaders. I guess he was only short of queen Elizabeth, which doesn’t seem a very apt comparison—he wasn’t a monarch, of course, he was a leader of a revolution. It was a combination of extraordinary charisma, nationalism, and authoritarianism that managed to keep him in power. Fidel had the luxury of Cuba being being an island, and him being able to let many of the people who might organize against him simply leave or flee the island. Over the course of a number of years there were repeated immigration crises. Fidel opened kind of an escape valve for tens of thousands of people to leave—very dangerously of course, many times, like the Balsero crisis—and many others have simply left Cuba. But of course the vast majority of Cubans stayed, and some of them benefited tremendously from the revolution. Others did not.

Gilsinan: Who benefited from the revolution?

Kornbluh: Many of the people who lived in the rural countryside, [people who] had no access to health, education, clean water, housing. You need to remember that Cuba was a relatively well-developed Caribbean island before the Cuban revolution, but there was a lot of social expectation and a tremendous amount of inequality. Just to give you an example, Cuba imported more Cadillacs than any other country in the word, for the wealthy class and for the U.S. elites who vacationed and lived in Cuba. After the revolution Fidel famously announced, “We don’t need Cadillacs. We need tractors.” And he banned the import of all new American cars and transferred the money that would have been otherwise used by the state for those types of imports to buying agricultural equipment and making an effort to develop the countryside—building housing in the countryside, schools, hospitals, and creating educational opportunities for Cubans, that particularly rural Cubans would not have otherwise had.

Gilsinan: To talk about Cuba as a global power, how did he manage to wield such disproportionate influence, relative to his position at the helm of this small island that became increasingly poor following the revolution? To what extent was this the power of being able to stick it to the United States so consistently?

Kornbluh: I think this is Fidel Castro’s greatest legacy: transforming Cuba from a regular-sized Caribbean island into a player on the world stage completely disproportionate to its geographic size and location. While there is no doubt that while the impact of Fidel’s vision and socialist principles on Cuban society will be debated for years if not decades to come, his impact on Cuba as nation in the global arena, as a sovereign, proud, and supportive nation on kind of the correct side of history if you will—supporting the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa; the efforts very early on [supporting] small groups of guerrillas called the Sandinistas to overthrow the brutal and greedy Somoza dynasty in Nicaragua; having kind of the Cuban equivalent of Doctors Without Borders, sending tens of thousands of doctors around the world on free medical missions, to be supportive of other communities that didn’t have access to doctors—Cuba really gained in tremendous prestige, influence, and impact.

And that is completely indisputable, and you’re going to see that in the outpouring of condolences from world leaders today today, and in the presence of many of those leaders at the memorial service for Fidel. And Cuba today is a proud country, and a respected country, throughout the region of Latin America and in the Third World. You’ll see the quotes from Nelson Mandela, for example, who said, we can’t even put into words the importance of Cuba’s support for our movement. The United States found itself on the other side of the anti-apartheid movement. In the confines of the White House and the Oval Office Henry Kissinger referred to Fidel Castro as a pipsqueak, denounced him for his role in Africa in the mid-1970s, and actually developed contingency plans to invade Cuba. But on the world stage Fidel Castro was a giant. He was the David versus Goliath when it came to Cuba versus the United States.

Gilsinan: Not in all cases on the right side of history, right? Certainly not on the right side of the Cold War, and elsewhere in Africa—Angola, for example.

Kornbluh: His role in Africa and Angola was an anti-colonial role, but the CIA was on the other side, really, and Kissinger as well. If you look at the history carefully, the Eisenhower administration kind of pushed Fidel right into the arms of the Soviets. They were kind of thin-skinned about his anti-American rhetoric. They’d never known a Latin American leader to say the things that he said about the United States, and his impudence at the time—his willingness to say, “Why should Cuba have to play by one set of rules, where you tell us what to do and you get to do whatever you want? We’re a sovereign country, and the revolution means that we can act independently, that’s what the revolution was for.” And he was constantly reminding the United States of this issue, every time a president would say let’s negotiate better relations, here’s what we want from you—you know, get out of Africa, or terminate your relationship with the Soviet Union—Fidel’s response would be, “I don’t tell you how to run your foreign policy, and I don’t deserve to be told how to run mine.”

Gilsinan: When in your view was the best opportunity not to, as you say, “push Cuba into the arms of the Soviets”? You’re saying that that wasn’t inevitable?

“We were all Fidelistas. Until after the revolution when you lined those guys up at the wall and shot them.”

Kornbluh: If you look carefully at the Eisenhower era and the early months of the Kennedy administration, you’ll see that the CIA started to plot overthrowing Castro about six months into 1959, after Castro had come to visit the United States on an extended visit. When Castro was here the CIA secretly met with him and tried to recruit him to try to identify the communists in his government and get rid of them. It wasn’t always that the CIA and U.S. government officials were against Fidel; the CIA initially saw him as a spiritual leader of democratic forces in Latin America. Batista, who he overthrew, was such a thug. I worked with Fidel and his office on organizing 40th-anniversary of the Bay of Pigs [in 2001]. And we took the deputy manager of the CIA’s Bay of Pigs operation, Robert Reynolds down to Cuba, and I arranged for him to be the first speaker at the conference. He sat across the conference-room table from Fidel, and said, you know, when you were in the Sierra Maestras [with] the guerrillas, fighting to overthrow Batista, I was a member of the CIA’s Caribbean task force, and we were monitoring your progress. And we all saw you as a very romantic figure. He looked at Fidel and he said, “We were all Fidelistas. Until after the revolution when you lined those guys up at the wall and shot them.”

Gilsinan: That was the turning point?

Kornbluh: There was a series of turning points. The executions were not really the turning point, but they became kind of a propaganda asset for the Eisenhower administration. Fidel was unbelievably furious about this because there hadn’t been a single statement in the press about how Batista was butchering innocent Cubans for years, and the United States had supported him endlessly while he was doing this. And then Fidel comes in and the revolution succeeds, at tremendous bloodshed and cost to many many Cubans, from Batista’s bombing with U.S. planes, U.S. bombs given to the Cuban air force. And then suddenly human rights was an issue after the revolution, when it never was before.

The turning point was the agricultural reform, which nationalized land that was held by U.S. agricultural corporations, and a lot of Fidel’s rhetoric and anger, which U.S. officials couldn’t really see past. And kind of an overreaction to the first Soviet mission to Cuba, which at that point was not a military relationship. Fidel only declared Cuba a socialist state after the preliminary attack in the Bay of Pigs, at the point he understood that they were going to be attacked by the United States. At the funeral of the initial Cubans who were killed in what was considered the first airstrike, to take out his air force, by the CIA, he announced that Cuba was going to be a member of the socialist bloc and he basically called on the Soviet Union to protect them. But the actual assault came that night. There was no military relationship between Cuba and the Soviet Union until after that point. And then of course, because of that attack, Fidel was for more predisposed to accept the Soviets’ offer of nuclear missiles to deter another attack.

Gilsinan: How much has changed since Fidel stepped down?

Kornbluh: Quite a bit has changed in Cuba since Fidel Castro stepped aside 10 years ago. He was felled by a severe case of diverticulitis, two botched operations, internal septic shock—he almost died twice. His brother took over in what was a seamless transition of power—shows you very clearly that this wasn’t just a one-man rule in Cuba, it was very institutionalized, the Communist Party system. Those who somehow hope that now that Fidel has died there will be upheaval or political change in Cuba are going to be disappointed.

“Cuban society certainly is evolving economically. And somewhere down the line that is going to have a cultural and political impact.”

But much has changed. That’s another reason I don’t think there’s going to be the upheaval that some people actually want, in the United States. Raul Castro understands that in order to have what he calls “sustainable socialism” you have to be able to generate resources that can be distributed, and the state is not able to do that. He has created a private sector which now accounts for almost 27 percent of the Cuban workforce; it’s largely tied up in tourism, but not completely. It continues to grow, but very slowly, in some ways too slowly for the Cuban population that has waited a long time, and has had its expectations raised by the normalization of relations with the United States. But with the social and economic changes changes under Raul Castro, Cuban society certainly is evolving economically. And somewhere down the line that is going to have a cultural and political impact. But things have changed. At this moment we have a normal U.S.-Cuban relations of sorts, the president of the United States has gone to Cuba—I had the great honor of going with the White House press corps with him—and it’s been an extraordinary dynamic. That dynamic was already kind of under a shadow from the new president-elect, before Fidel died last night.

Fidel’s death has kind of put Cuba on the agenda in a dramatic way. The fight over his legacy one that’s going to require Trump taking a position—obviously the Cuban American community, hardline Cuban Americans in Congress demanding that Trump reverse what Obama has done and punish the Cubans for whatever. So there’s a dark shadow falling over the extraordinary initiative taken by Raul Castro and Barack Obama, that’s now almost at its second anniversary, with everybody wondering, will Donald Trump be the businessman and see the positive side of continuing commercial and economic relations with Cuba in a normal way? Or will he be the political figure who makes good on his campaign rhetoric of “reversing” Obama’s executive orders unless Cuba “meets our demands”?

Of course the whole history of Fidel Castro’s leadership and life is that Cuba doesn’t yield to the demands of the United States of America.

Gilsinan: Has Trump made any specific demands?

Kornbluh: He only made them in the context of trying to win the Cuban American votes in Miami, saying that his demands were going to be for religious freedom, political freedom, etc. Whether there’s been any back-channel discussion between the United States and Cuba so far, I don’t know. The Obama administration opened up this extraordinary back channel to Cuba, as the title of our book suggests, and that channel is still open. And I assume that messages have still been passed through it, regarding the incoming administration. But what Castro’s death does is takes kind of an issue that was going to stay kind of low-profile and down on the totem pole of Trump’s agenda, which would have allowed quiet communications and kind of a “let’s get to each other” kind of period after Trump was sworn in, to now being something that loud and noisy and high-profile and contentious, and that will only continue through the period of the memorial service in the coming days for Fidel Castro, and that’s too bad.

For all the narrative of him waving his fingers and screaming about those awful Yankee imperialists, he understood that the security and validity of of the Cuban revolution would be safeguarded through normal, respectful relations with the United States. And he reached out to every president since Kennedy, quietly, secretly, every once in a while publicly, to say, “As long as you treat us with respect, we’re willing to talk to you about what your interests are.” And the documents are indisputable on this—we have all the messages that he sent to Kennedy, to Lyndon Johnson, to even Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. They show somebody who was really was very invested in a better relationship with the United States—not to the point of sacrificing his revolutionary principles, but in saying that coexistence was possible. I think that’s the message now that the Cubans hopefully will be able to send, and that will be received positively by the incoming administration.

Gilsinan: Are you hopeful about that?

Kornbluh: No, I’m not. I’m not as hopeful as I would like to be. Obama has worked very hard to make this normalization process irreversible—he has opened the doors to travel, he has gotten the airline companies invested, he’s gotten some of the hotel companies invested, he’s gotten some of the agricultural interests in various key Republican-dominated states invested in a process of better commercial relations. So he’s trying to make it a lot harder for Trump to simply dismiss all of this and reverse it. When you go back to the history of U.S.-Cuban relations and you see that really the breach in relations came over rhetoric, and thin-skinned U.S. officials—you know, we’ve got the most thin-skinned U.S. president-elect probably in the history of the presidency at this point. And somebody who loves to be a bully, and somebody who plans to bring new meaning to the expression “the bully pulpit” of the presidency. I am worried, because of Cuba’s defensiveness, and because Cuba refuses to be bullied, I am worried about how quickly the situation could deteriorate. I’m worried that it will, but hoping that it won’t.

END

Be the first to comment