Even as ethnic loyalities run deep, however, voting choices may not necessarily be ethnically homogenous. Considering Deputy President William Ruto is a more influential Kalenjin, Mr Isaac Ruto, who has boasted of bringing at least one million Kalenjin votes to the table, cannot be so confident, for instance. And the voters’ register does not necessarily reflect the exact tribal configuration of the population.

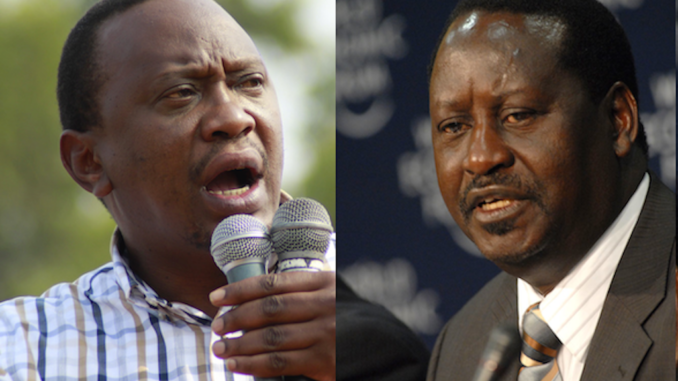

Two very close opinion polls on the frontrunners of the 2017 Kenyan presidential election just weeks to the August 8 vote made writ large how potentially contentious the outcome could be. For the first time since campaigns began, one poll had the leading opposition candidate, Raila Odinga of the National Super Alliance (NASA), ahead of incumbent president, Uhuru Kenyatta of the Jubilee Party. The Infotrak Harris opinion poll conducted between July 16 and 22 put Mr. Odinga ahead of Mr. Kenyatta by one point, with the former rising in popularity to 47 percent, a three-point gain from about two weeks before. Mr. Odinga’s improved chances stemmed from holding on to his key support base, as well as securing new supporters from what used to be the Rift Valley and North Eastern provinces (now a couple of counties), strongholds of the ruling Jubilee Party. Another poll, that by Ipsos, taken from July 2 – 12, put both leading contenders at a tie at 45 percent. The Ipsos survey was probably behind the curve in light of its earlier date. Judging from how the media initially under-reported Mr. Odinga’s gains, the establishment was clearly shocked.

Not long thereafter, Mr. Odinga made a surprise appearance at a televised presidential debate that he and Mr. Kenyatta had earlier indicated they would not attend. There was much concern about the reluctance of the candidates to debate each other ahead of the elections. In the vice-presidential debate, for instance, only one candidate showed up. Independent deputy presidential candidate Eliud Muthiora Kariara debated himself in mid-July as his rivals found excuses, ranging from disagreement with the format to not being formally invited, for staying away. Mr. Kenyatta’s no-show at the debate was a little surprising considering his campaign cancelled an earlier scheduled trip to Samburu and Marsabit districts in the former Rift Valley and Eastern provinces respectively on the day of the debate. His decision might prove costly: Mr. Odinga had the stage entirely to himself. In his defense, Mr. Kenyatta asserted the debate would have been a waste of his time, preferring as he put it, to be commissioning projects. NASA stalwarts think he simply fell for their trick: Kalonzo Musyoka, Mr. Odinga’s running mate, said he deliberately stayed away from the deputy-presidential debate in a calculated scheme to snare the Jubilee camp into thinking the head of the NASA ticket would similarly not attend the presidential one. They probably have a point, because it is highly unlikely Mr. Kenyatta would have ceded 90 minutes of primetime television and radio to his opponent otherwise.

Whether Mr. Kenyatta’s debate miss would have an impact on the election results remains to be seen, however. But should Mr. Kenyatta lose the election, one of the reasons would almost certainly be because he allowed Mr. Odinga to have the undivided attention of the country for more than an hour, without the chance to make his own case. Such is the level of uncertainty now that there is talk of a likely second round vote. And even before the debate upset, an objective assessment would have revealed Mr. Odinga was probably in a far stronger position than the media, or in fact the opinion polls, suggested. Mr. Odinga’s coalition of popular politicians from the major ethnic groups, his populist rhetoric, and the electoral reforms he successfully pushed for, could sufficiently tilt the balance in his favour. That is, barring any major adverse events, of which there are already a few. An ongoing cholera outbreak and the perennial terrorist threat from Somali Al-Shabaab militants are examples of threats that could instigate measures by the authorities with potentially dampening effects on voter turnout on election day.

Ethnic Arithmetic Favours Opposition Coalition

Although the 2017 elections would be the second since the new 2010 constitution, which allowed for the devolution of powers to the counties, was adopted, it would also be the first since citizens got a taste of how much power the counties now wield. And it is increasingly obvious a couple of counties might decide the election, judging from the amount of time the two leading candidates dedicated to them during the campaigns. They are Narok, Kajiado, Kisii, Baringo, and those in the former Coast and Western provinces. Even so, a lot of voters are expected to decide along ethnic lines. Mr. Kenyatta, who is Kikuyu, the country’s largest tribe and 17 percent of the population (2009 census), and his deputy, William Ruto, who is Kalenjin (13 percent of the population), could easily secure 30 percent of the vote, based on their joint ethnicities alone. Mr. Odinga, who is of the Luo ethnic group (10 percent of the population) and the other four principals of the National Super Alliance (NASA) coalition, namely: former vice-president and deputy prime minister, Musalia Mudavadi of Luhya ethnicity (14 percent of the population), former vice-president, Kalonzo Musyoka of Kamba ethnicity (10 percent of the population), former Senate minority leader Moses Wetangula of Luhya ethnicity and Isaac Ruto, who is a Kalenjin, could together easily secure 47 percent of the vote if their ethnicities are reliable proxies; albeit only Mr. Musyoka is on the presidential ticket with Mr. Odinga.

Even as ethnic loyalities run deep, however, voting choices may not necessarily be ethnically homogenous. Considering Deputy President William Ruto is a more influential Kalenjin, Mr Isaac Ruto, who has boasted of bringing at least one million Kalenjin votes to the table, cannot be so confident, for instance. And the voters’ register does not necessarily reflect the exact tribal configuration of the population. That is, some tribes might have a greater representation on the register than their share of the population and vice versa. Besides, voter turnout on election day might not be similarly structured. And the loyalties of tribes like the Kenyan Somali (six percent of the population) might go either way, although they may not forgot too soon the court-botched closure of the Dadaab refugee camp by the ruling Jubilee government.

Past election results could also be an indicator of how the candidates might fare this time around. Mr. Mudavadi, who is not contesting for elective office in the upcoming polls, secured 3.96 percent of the 2013 presidential election votes. If summed with Mr. Odinga’s 43.7 percent, their joint tally of about 48 percent, though impressive, would still fall short of the minimum 50 percent and one vote needed to secure a victory, however. That is in addition to having more than 25 percent of votes cast from at least half of the country’s 47 counties. But add those that could potentially come on the back of the other NASA prinicipals, an extra two percent might not be that difficult. In contrast, Mr. Kenyatta cannot be assured he would get as much as the 50.5 percent of the vote that he got in 2013. Myriad allegations of corruption, a drought-induced grain shortage (albeit now ameliorated with government-subsidised imports) and so on, have likely eroded some of his support. It is also probable Mr. Odinga’s populist and socialist rhetoric resonates more with voters than Mr. Kenyatta’s capitalist drift.

From April 2016 onwards, Mr. Odinga and his supporters staged several protests demanding changes at the IEBC that would ensure the umpire is not in a position to fraudulently tilt the election in favour of the incumbent. After a few deaths, the ruling Jubilee government agreed in August 2016 to replace the IEBC commissioners, which the opposition called biased.

IEBC Must Be Beyond Reproach

With such a tight race, much would depend on whether voters trust the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC). What is significantly different this time around though, is that the election results declared at polling stations would have finality, as opposed to the past practice of making them provisional to final certification by the IEBC in Nairobi. That much the courts have affirmed: the IEBC failed in its appeal of the April 2017 court ruling which ordered that results declared at polling stations must not be subject to change at the national collation centre. Such a decentralised system makes it more difficult to cheat, as all stakeholders would be able to do their own collation based on the same constitutency-level results. The increased transparency, consequently, is also why fears of violence may be overblown. Credit for these laudable changes must go to Mr. Odinga and his coalition partners.

From April 2016 onwards, Mr. Odinga and his supporters staged several protests demanding changes at the IEBC that would ensure the umpire is not in a position to fraudulently tilt the election in favour of the incumbent. After a few deaths, the ruling Jubilee government agreed in August 2016 to replace the IEBC commissioners, which the opposition called biased. One month later, Mr. Kenyatta signed into law amendments to the electoral act that included new criteria for recruiting IEBC commissioners.

Despite these gains, Mr. Odinga and his coalition partners did not relent in their scrutiny of the IEBC. When the ruling Jubilee government would not budge on an issue, the opposition simply went to the judiciary for redress. Mr. Kenyatta did not hide his irritation, as the courts seemed to be ruling more often in the opposition’s favour at some point, forcing a word of caution from Chief Justice David Maraga. Jubilee Party tried to cast doubts on the credibility of at least one judgement unfavourable to it, citing the conflict of interests. Court of Appeal judge William Ouko, who was one of the five-member bench that ruled on the finality of election results at the constituency level, is related to Mr. Odinga’s wife, for instance. The niece of one of the NASA lawyers turned out to be married to one of the judges in another case that NASA won. Were that to be a yardstick, however, then almost all the top judges could be conflicted. It is typical of the elite in the private and public sectors to inter-marry; after all, they often belong to the same social circles. Unsurprisingly, when the courts have been unfavourable to Mr. Odinga, he has similarly accused Mr. Kenyatta of intimidating the judiciary. The key point here is how deliberative combative both sides have been and how determined they are to win.

Procurement activities at the IEBC have also been marred by one controversy after another. It cancelled the tender for poll equipment in March 2017, for instance, amid accusations of corruption from the opposition. The awarding of the contract to print ballot papers to Dubai-based Al Ghurair, a company NASA claims has ties to Mr. Kenyatta, is another, a charge the firm denies in a sworn affidavit. A high court ordered Al Ghurair to stop the printing of presidential ballot papers regardless, but this was later overturned on appeal as the IEBC expressed fears the elections could be delayed. The controversy could have been avoided in the first place if proper tendering processes were followed. Because even before the Al Ghurair saga, the tender had been cancelled at least twice over irregularities, forcing the IEBC to send erstwhile procurement director, Lawy Aura on compulsory leave in June 2017. Information Technology director, James Muhati, received a similar treatment at about the same time, when it emerged he was not being helpful with a systems audit. His replacement, Chris Msando, was found tortured and murdered in late July, a little over a week to the polls and just before a systems audit was scheduled. Although, the IEBC has since discountenanced suggestions of a disruption consequently, it would be difficult to put in place another senior staff with the same level of competence, preparedness and, as was found, high integrity, within such a short period. Besides, it is highly improbable that Mr. Msando’s assailants would have taken such a drastic step if they were not convinced that his replacement would either be less competent or prepared or more pliable. Regardless, they likely succeeded in getting enough information on the so-called Kenya Integrated Elections Management System (KIEMS) through torturing him. Thus, unless there is a re-configuration, KIEMS has likely been compromised. The proximity of the killing to the poll date also means a new ICT manager would not have enough time to gain the trust of the public, like Mr. Msando was able to. In fact, NASA has expressed fears the transmission of the election results may be hacked. To forestall this, it has asked that an independent international firm be tasked with overseeing KIEMS. IEBC chairman, Wafula Chebukati disagrees, insisting the commission’s systems are secure and a competent team remains in place to ensure hitch-free elections. Mr. Chebukati could not be so sure that early on before the conclusion of substantive investigations. For an election considered to be Kenya’s most expensive yet, these negative events are quite concerning.

There are currently more than 300 cases at the courts against the IEBC. The major ones, that is, those that could have delayed the elections, have been addressed, however. The one that relates to the printing of presidential ballots was earlier highlighted. Another suit by NASA asking the courts to stop the IEBC from using a manual voting system as back-up, has also been quashed. The worry of NASA, of course, was that a manual system would be open to fraud. It had hoped voting would be exclusively electronic. But in light of the Nigerian experience where electronic voting kits failed on election day, it is probably wise to have a manual back-up. That is even as Jubilee Party may likely want the manual system backup for sinister reasons. What NASA had wanted was for the IEBC to postpone the elections should the electronic kits fail. This it hoped would demotivate any shenanigans like the electronic kits being made to deliberately fail just so the elections would be largely manual. Still, the myriad litigations even before an actual vote point to a potentially contentious election aftermath. It is a positive that at least the key questions that hitherto put a cloud over the elections, have been answered by the courts.

Potential Turnout Holdups

A spreading cholera outbreak is not helpful either. From the beginning of the year to 17 July, there were already 1,216 registered cases and 14 deaths. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has classified it as high risk nationally and regionally. Should it deteriorate further, necessary quarantine measures would disenfranchise a swathe of voters. The authorities have already shut down venues where cases have been recorded and ordered the testing of about half a million people in July. More stringent measures are probable. Furthermore, elections are being held this year amid a still challenging food supply environment. Government-sponsored imports to ameliorate the problem have been largely effective, though. But the arrangements have tended to run into problems from time to time. In July, for instance, wheat prices rose on higher demurrage charges to ships carrying imported supplies, but were delayed at the ports. A two-kilogramme packet rose as much as 11 percent to 133 shillings from 120 shillings two months earlier. The food crisis came in handy for Mr. Odinga, who harped on past warnings about the country’s dwindling grain reserves. A refusal to lift trade barriers with neighbouring Ethiopia to favour the Jubilee Party acolytes’ maize import arrangements with Mexico, was fingered.

…if the IEBC succeeds in being as transparent as it has promised to be, earlier anxiety ahead of the polls might quickly translate into an aggressive push to regain lost economic ground afterwards. And what was largely city-centred violence in the aftermath of the bloody 2007 elections, could supposedly not be the case this time around.

Economic Costs Not Likely as High Despite Fears

Historically, Kenyan economic growth suffers in election years. There have been exceptions. In years when electoral reforms preceded the polls, there was no material negative economic impact that could be attributed to this. Typically, however, there is a 60 percent chance of a growth slump in an election year, if analysis based on World Bank and Kenyan National Bureau of Statistics data from 1990 is anything to go by. So it is not too surprising that expectations are rife that this might also be the case for the 2017 polls. And the recovery has tended to range from 18-26 months, depending on whether the elections were single-party or multi-party based. But the election-related slumps theory has not proved to be robust post-2002. True, growth was -1.1 percent in 1992 from 1.3 percent the year before. Similarly, growth slowed to 0.4 percent in 1997, another election year, from 4.2 percent in 1996. Growth also slowed to 0.5 percent in 2002 from 4 percent in 2001.

Interestingly, even with the violence that characterised the 2007 elections, growth actually rose higher to 6.9 percent that year from 5.9 percent the year before. This was also the case for the 2013 election year, which saw growth up to 5.7 percent from 4.6 percent in 2012. So, there is room to contend that growth might actually not suffer as much in the current election year. Most economic growth forecasts for 2017 remained around the 5 percent area a month to the elections despite these concerns. In its July 2017 update, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) put its forecast for 2017 at 5.3 percent; albeit lower than the 6 percent estimate for 2016.

Besides, if the IEBC succeeds in being as transparent as it has promised to be, earlier anxiety ahead of the polls might quickly translate into an aggressive push to regain lost economic ground afterwards. And what was largely city-centred violence in the aftermath of the bloody 2007 elections, could supposedly not be the case this time around. This is because as more power has been devolved to the counties since then, what is probable could be no more than small pockets of violence here and there at the local level, and not the type of co-ordinated anarchy in 2007.

Regardless, some remain convinced that there could be even more troubles this time around. One theory revolves around the intergenerational family rivalry between the Kenyattas and Odingas. Mr. Odinga would be contesting for the fourth and likely last time, but second time against Mr. Kenyatta. After a remarkably strife-filled political life ranging from imprisonment to exile, Mr. Odinga is putting everything into this election. There is a family history that Mr. Kenyatta is seeking to guard as well. Mr. Kenyatta would likely be heartbroken if it turns out he lost to Mr. Odinga, the son of his father’s arch-rival and who, like his father, he has managed to prevail over thus far.

Currency speculators, who are almost convinced the shilling would suffer losses over worries of a violent vote, have been having a field day. The Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) governor Patrick Njoroge has warned they would get their fingers burnt, pointing to ample foreign exchange reserves boosted by an IMF standing facility precisely for such potential shocks.

Still, economic activity has slowed owing to the upcoming polls. Manufacturers have been reducing their throughput and investors have not been investing as much. International trade has also recorded dampened activity, as landlocked neighbours, who usually pass their cargoes primarily through the Mombasa port, have been diverting them to the Dar es Salaam port in Tanzania. There is historical precedence for these actions. In the aftermath of the 2007 election violence, Ugandan and Rwandese traders reportedly lost 158 billion shillings, compensation for which the Kenyan authorities had no choice but to oblige. This time around, it does not seem like they are taking any chances.

Travel advisories have also been issued by foreign governments, with multinationals reportedly giving their staff leave to move to neighbouring countries a week before and stay until a week after the polls.

Rafiq Raji, is an adjunct researcher of the NTU-SBF Centre for African Studies, a trilateral platform established by Nanyang Technological University and the Singapore Business Federation.

This article was by the NTU-SBF Centre for African Studies on 4 August 2017. It was also by published by Africabusiness.com.

END

Be the first to comment